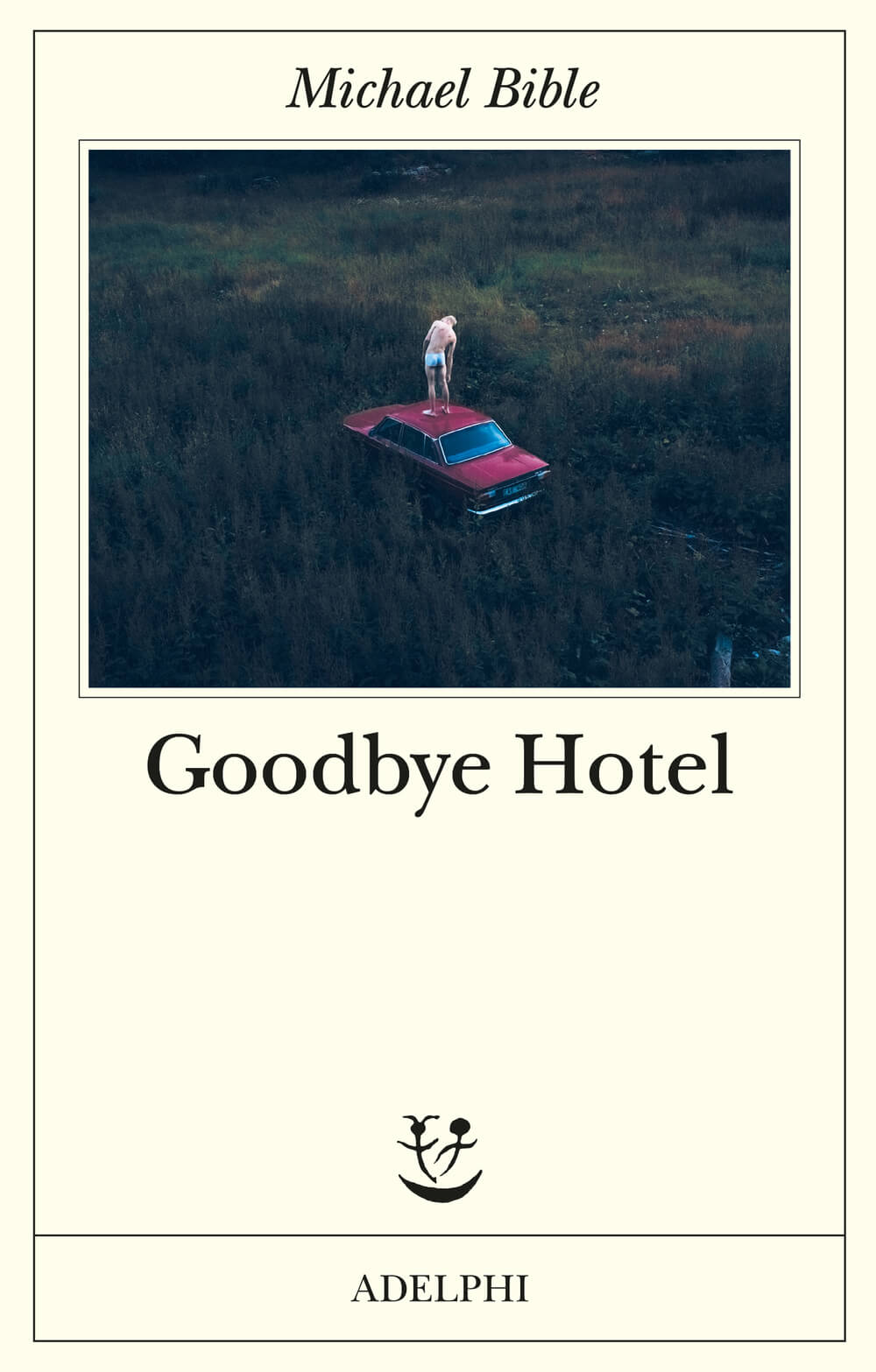

There’s something deeply magnetic about the way certain writers can transform pain into beauty, solitude into contemplation, and destructive fire into purification. In this intimate and revealing conversation, Michael Bible, author of “Goodbye Hotel” opens the doors to his creative world, a universe where the past is never truly past, as Faulkner said, and where memory becomes the silent engine of every story.

From the pages of his latest novel emerges a mosaic of lives that interweave like constellations, stories that catch fire and burn out while only the turtles survive the millennia, silent witnesses to passing humanity. But behind this cosmic narrative lies a profoundly human reflection: that of a writer who has made solitude not a curse, but a choice born of love for himself and his art. It is in this sought-after and beloved solitude that his “little empathy machines” are born, his term for books, poems, and music, instruments capable of showing us that, deep down, we’re not all that different from one another.

Through his words we discover a man who doesn’t write, but transcribes; who doesn’t invent, but records what is whispered to him from the silence of contemplation. An artist who finds in nihilistic philosophy a paradoxical source of hope, who sees in fire not only destruction but cleansing, and who considers innocence not as naïveté, but as the courage to welcome life with open arms. In an age where truth seems increasingly elusive and happiness is confused with social media perfection, this writer reminds us that true joy comes from accepting even the negative, that forgiveness liberates the giver more than the receiver, and that, quoting his teacher, “heaven is pals.”

“Goodbye Hotel” begins with a phrase, a concept that I find amazing: it tells us about chaos and order that originated everything, it asks us to imagine the past, a moment in which all possible things exist simultaneously, even if they then take a direction. What relationship do you have with the past? Is it something that helps you, inspires your work?

Yeah. Faulkner has a great quote, “The past is never dead, it’s not even past.” And I think there’s a sense, to me anyway, that the past is always with us, in many, many levels. In the historical level, being from the South, certainly the past is a very immediate thing that we deal with. But also just within the spiritual life, memory drives a lot of what I do and what I’m curious about. So, the past is very important, but I also am very interested in the future.

Still in the first pages, you say that one is never alone if one has the ability to dream: is solitude something you like to approach or is it something that frightens you?

Quite the opposite. I relish being alone. I don’t really know if I have any talent as a writer, but I certainly have a predilection towards spending a lot of time alone. And all writers do; it lends itself to writing. So, I found something that suited my love of solitude, and not just solitude, but contemplation and doing nothing. Trying to sort of find that silence and that peace. It’s really, it’s a constant search.

I also really liked when you wrote about “the invention of God,” putting it on par with the invention of art, for example. In your books, biblical figures and religion in particular are described very often and often not in a positive way, faith almost becomes an impediment to seeing the truth. And above all, people who are part of religion don’t truly feel empathy for others. How important do you think empathy is nowadays? Do you think having more of it could also help us have “a better world”?

I do. And I think it’s not just important, it’s essential. I think we have to be able to see how other people are suffering, even if those people are doing horrible things. Because those horrible things are coming from some place. And if we’re able to see that, I think that we can understand each other a little better. I hope that art, music, cinema, poetry are the bridge.

To me, books, novels, poems, music, they’re little empathy machines – they show us that we’re not all that different when we get down to it.

“Goodbye Hotel” seems to be a constellation of stories, moving from one to another, everything catches fire, is destroyed, and only the turtles survive the millennia, watching humanity with their gaze. How did you come up with the idea of telling this story made of a thousand stories?

It’s hard to know. But I think that, to go back to the contemplative life, if you’re open and patient, and you’re still, a lot of wonder can enter your life. And if you’re able to see that wonder, writing becomes something that’s really just transcription. A lot of artists talk about this, and it’s a very hard thing to describe, but it doesn’t feel that I’m actively writing, it feels that I’m just recording what’s being told to me. But that’s a hard place to find, and I’m constantly seeking it. That is how I work.

Truth is also an important aspect of the book, especially the lack of truth. In your opinion, is it important to always have the truth in one’s hands, especially as writers or readers? Or is being “deceived” somewhat part of the game?

Well, I think all writing is an act of deception in some way, or a lie that’s telling a deeper truth. Truth is difficult to arrive at, and there are many types of truth, and many different truths, and everyone has their own version of truth. In fiction, I think that just when you think you know what’s happening, maybe the ground is shifting beneath your feet. To me, that’s true to life. That’s how I often, as I get older, I understand that things are not as they seem.

When you talk about Little Lazarus’s memories, you suggest that the memories these wonderful beings have are deeper and more primordial than those we humans have. If you could experience a memory in that way, would you? Or have you ever felt so deeply connected to a memory?

Yeah, I’m in some way haunted by certain things, and I don’t mean that in a negative way, necessarily. You know, people say that when you remember something, you don’t actually remember the event – you remember the last time you remembered it. And so, it’s like a “game of telephone”. It changes a little bit each time. So, to go back and try and recover it is this act of creation, this act of myth, this act of storytelling.

Fire is also the protagonist of your novel “The Last Beautiful Thing on the Face of the Earth,” but here it expands even more: not only is it the fire that eventually envelops everyone, burns everything and cleans everything up, but it’s also in the characters’ heads, like François who says that it seemed like everything in his head was going up in flames. Can we say that the fire in “Goodbye Hotel” is the same that pervades your previous novel?

The same fire, you mean? Interesting. I guess in some mythical way, all fire is the same fire, you know, deep down. It’s kind of passion, you know? Fire to me is this wonderful thing sometimes.

It’s scary to me.

Yes, it’s scary, but it’s both destructive and cleansing at the same time. I’ve always been fascinated by fire, and, you know, I grew up around building fires, which is a wonderful place of contemplation. Also, I know a lot of people that work in forestry, and they clean with fire, you know? The underbrush is burned away so that new things can grow and so that there’s not so much fuel for wildfires. I think it’s a metaphor for “the thing that you’re afraid of is not always negative”. And it doesn’t always have to stop you from doing things.

One of the recurring themes is also that of “desiring the impossible”. What seems impossible to you today?

A lot of things. We’re living in really dark times, troubling times, but I think that real hope can only come in those desperate times. To really seek something that has not yet happened, or we can’t even comprehend happening, and being open for that possibility is the way that we can get through it. You know, hope without optimism. Optimism, I think, demands a conclusion, that something good will happen. But hope says, “I’m open to whatever it is, and if it’s negative, I’ll get through it. If it’s positive, I’ll learn”. To me, hope is a very complex thing, but it’s essential, it’s important.

You know, there’s an old anarchist phrase, “Demand the impossible”. And I think if we’re not willing to at least envision a world that’s different than our own, we’re going to be stuck in the world that we have.

Walt’s character says he was healing from his addictions and illnesses thanks to his search for the beauty of art. Do you really think that art, as well as literature, can save or heal? Has it ever happened to you?

Oh man, absolutely. So many things have dragged me out of dark places, literature certainly has, music certainly has, writing and playing music certainly have. Painting, which I’m terrible at, but enjoy to no end, has taken me out of it. And also recently, philosophy. I’ve never been attracted to philosophy or philosophers, I’m not a person of great intelligence, I always saw philosophy as very complex and difficult, but recently I’ve discovered nihilistic philosophers that, to me, give me great hope and are very liberating.

I think you’ve got to be open, and you’ve got to be always at the ready for that new possible thing. And literature is full of that, art is full of that, music is full of that.

All the characters stay on the page for the time of a flash but form a puzzle that completes itself. Is there a character you would have liked to “keep around longer”?

You know, those characters were fun to write, but maybe Walt. Yeah, maybe spend a little more time with him and see what he was up to. That character of a sort of a frat boy turned artist is interesting.

At one point, Lazarus finds himself envying the short life of flies, saying that every second would be sweeter and simpler: no more projects, no more worries. Death is obviously a topic that is often addressed, along with the concept of time. Does the passing of time frighten you?

No. You know, there’s a Japanese phrase, “Mono No Aware”, the beauty of impermanence. You need to be open to those things, to seeking them, to just the moment here we have together, you know, with the rain falling, which is a magical kind of a thing, beautiful and dangerous… I think the important thing for me as I’ve gotten older is to really relish and savor life and look for things that, while they might seem on the surface difficult, are actually deeply absurd and funny and silly things. And I think if you can arrive at that place, life becomes a sort of a river, you know, it’s a song.

Lazarus is slow but in constant movement and seems to be the only one to remain while people come and go, the turtles are the only ones to see everything. Perhaps our existence as human beings leaves no mark?

I think we do leave a mark. I know so many people that have been in my life that I’ve lost, that have rippled their existence and their loss creates a void. And in that void, the people that knew them come closer together.

It’s happened to me again and again and again. But, you know, I’m not afraid of the idea of not existing. I think that that’s the most human thing there is, that we’re all going to expire. That should make us want to become closer while we’re here and not put this sort of genuineness and this joy away to another time.

Sugar says that life is all already decided, free will doesn’t exist, there’s no possibility of choosing. On the contrary, Lazarus says that one just needs to be open to the idea of something for it to happen, that willpower makes you have everything. Who do you agree with?

Well, I will plead the fifth and say: I leave that up to the reader. To be honest, I really truly am deeply agnostic, and I don’t mean in a religious sense. I mean in every sense of that word. It depends on the time of day, I think, but it’s something I think about a lot.

I was very moved by the part where Eleanor says it took decades to understand that she shouldn’t have blamed her father but should have blamed the world for the way it was made, for what the world had made happen to him to make him become what he was. It moved me a lot because I think it’s so liberating when you can separate your parent from who they should be, think of them as a person to whom things have happened, even horrible things. Maybe it’s the only way to forgive?

You know, particularly in America, where we have a lot of these violent episodes, people are very quick to separate themselves from them, to forget about it. We say they’re evil or they’re bad people or a narcissist, or they have mental problems or whatever. We don’t really think about the world in which they’ve grown up. I do think that having empathy for the situations that people are in can provide for a kind of forgiveness. But I also think you can provide for a kind of empathy and an empathy can lead to a forgiveness. But, you know, forgiveness isn’t about the person receiving it, it’s about the person giving it, and it doesn’t require anything other than the gesture of it.

I think it’s really important to forgive each other, forgive ourselves. We’re up against a lot, you know, there’s no manual for this and we were put here without asking to be. So, I think some patience and some empathy is always in order if we can get there.

There’s a quote I really liked from your book, saying that: “The difficult thing about being young is understanding what it is that you don’t know.” What do you think you still don’t know right now?

So much. There’s so much I want to learn. I want to learn Italian. I want to learn all sorts of things, you know, I’m fascinated by the world constantly. I seek innocence, I seek ignorance, I seek the possibilities of something new occurring. To me, intelligence is not all that it’s cracked up to be, I think intelligence is something that’s comparative. Well, it’s certainly claiming that it’s knowing something, but in order to know something, you have to have two things to compare. But innocence comes to life with open arms and says, “I’ll take whatever you give me.” It’s not always easy, but I try as much as I can to stay in that state of innocence or to return there. There’s a lot I don’t know.

Another beautiful passage of the book is where you say that happiness turns into tragedy and tragedy turns into reality and then reality turns into happiness again. So, do you think it’s just a matter of time when it comes to healing from a tragedy? Sometimes I think that it might not be possible to be happy again after a personal tragedy. But this phrase you wrote sounds really true.

Yeah, and, you know, it depends because, you know, we’d have to really drill down and think about what the word happiness means. I think there’s a deeper sort of complex joy that underlies fun and sort of happiness. And I think a lot of what we think about as happiness is everything’s going my way, everything’s smooth and perfect, and there’s nothing hard or negative about what’s going on in my life, but that’s not real joy, you know.

That’s a sort of surface-level happiness. To me, joy is a kind of deep satisfaction that welcomes negativity or problems and obstacles, not as things that are hurtful, but that are fulfilling. You know, I think about this in terms of writing a lot. I teach students, and I always use the metaphor of, “You don’t want to take a helicopter to the top of Mount Everest”. You want to climb the mountain.

The purpose is to climb the mountain.

So, particularly with young people, I think there’s a sort of longing for a sort of smooth happiness that they see online, where everything’s perfect and wonderful, and all these people are on vacation, and they all seem so happy, but we all know it’s fake. So, real deep happiness in relationships, with friends, with family, it comes with a lot of suffering and pain, and that’s what makes it all the sweeter and all the better.

Fear, especially in the final sentences of the book, is certainly a protagonist as well, but what is the thing that you fear the most?

I fear that I won’t be as open as I should be. I fear flying, alos, but, you know, I really push myself. I try and I push myself, and I don’t always get there, but fear can be a great help sometimes, and a great driver, but it’s all in our minds. It’s only something that we’re creating, and it’s a story that we’re telling ourselves, and we can just as easily tell another story.

And now, last question. What is your happy place?

You know, I have a wonderful friend, she’s a very amazing photographer in Mississippi, her name’s Jane Robertine. She’s lived there since the 80s, and they call her the Gertrude Stein of the South. She’s this wonderful host to artists and musicians and writers, and she has this unbelievable screened-in back porch that overlooks these fields, and on a night like today’s, rainy and stormy, you can watch the storm come in from the delta and pass through the hill country, and we just sit there and drink Budweiser and smoke joints and listen to old music and just say nothing.

Sounds like heaven.

It’s pretty damn good, you know? Dog at your feet, not too much to worry about, and good pals. My teacher used to say, “Heaven is pals”. I really believe that, I don’t think hell is other people. I think heaven is other people, so that’s my happy place.

Thanks to Adelphi Edizioni.