There is an invisible thread that crosses the ocean, connecting the mountains of the American desert to the shores of Marina di Castagneto Carducci. It is the thread of a conversation that arises from the urgency to speak the truth, even when it hurts, even when it disrupts the order of things. CJ Leede and Carlotta Vagnoli meet in this space of words where the literary horror of “American Ecstasy” interacts with feminist activism, creating a narrative fabric that explores the shadows of shame and sin that society imposes on female bodies.

This is a conversation about dangerous beauty and darkness that is not necessarily evil. It is a dialogue between those who find goodness in dogs and those who find it in sisterhood, between those who have learned anger through writing and those who have discovered mercy through living. It is the meeting of two voices that, from different shores of human experience, seek to answer the same question: what does it mean to be free in a world that always wants us guilty of something? Among Catholic rituals and transfeminism, between impostor syndrome and the revolution of imperfection, a discourse unfolds that touches the deepest chords of our time: how to stop being afraid to express who we truly are, how to build a democracy of authenticity in which no one has to hide anymore. Because in the end, when everything seems to collapse, perhaps the end of the world can truly be a new beginning.

First of all, CJ, congratulations for this new book, it’s one of my favorite readings of this year so far! I’m curious about the path that led you to this story and the character of Sophie, especially. Could you tell us about it?

CJ: I started this book when I didn’t even know that I wanted to be a writer. It was kind of a fluke situation, but I knew that if I was going to write something, it was about growing up with this kind of shame and sin kind of culture and the ways in which that was affecting me even as an adult. So, I think in terms of the book being horror and obviously speaking of a violent epidemic, that was the natural “extreme” of the idea that we tell young girls that their greatest value is their sexuality and sexual worth, but at the same time, it’s also their greatest sin and shame, and there’s a lot of guilt and shame around it.

I get what you say. You know, after reading “The American Ecstasy”, I reread “Memoria delle mie puntane allegre”. Carlotta, there you talk about the constant need for perfection requested by people who are part of the bubble of feminism. Thinking about your work, your activism, how can perfection be replaced by imperfection, the right not to be what is imposed on us, so to speak?

C: Well, it’s kind of what’s at the base of “The American Ecstasy”. We grow up with something that is imposed on us, the necessity of being always perfect. That’s why the female gender is much more likely to suffer from the impostor syndrome than the male gender. We always feel imperfect. The real revolution could be for us to look like shit, absolutely, but it’s unimaginable because obviously we would be excluded from the world of work, from the social world. Women are still very much under a magnifying glass in this sense.

Feminism is not perfect. Feminism should teach us to always question ourselves. Unfortunately, now we live in a political era in which they’re putting a lot of pressure on us, asking us to respond to everything that is happening in the world with a feminist interpretation. What they usually say is: “Where are the feminists?”. The answer is: where we’ve always been.

Imperfection could finally make human a movement that needs to be seen from a human point of view, and not from a mechanical or semi-divine point of view. We speak for human beings as human beings.

You just talked about the feeling of guilt, and I think about the past when Sophie’s mom talks about what happened to her and she says that it was her fault if that horrible stuff happened to her. I think that that feeling of guilt is unfortunately common among women and it’s so fucking unfair, obviously. What could help a change of perspective in that sense? Because it’s a cultural problem.

CJ: I think it starts with removing the “shame” aspect – you know, these are basic biological functions – and also removing this idea that anyone is responsible for any violence done to them or any unkindness done to them, male or female, is insane. So, I think those are the two big things. And probably education, that might help too.

C: Education is definitely a problem in Italy, education to sexual consent, education against gender stereotypes. Changing the narrative about violence might help, too: victim blaming is still perhaps the most practiced thing in our Western culture and women are still guilty for the crime they themselves have committed.

It’s a long journey. In the book, for example, in an “American Ecstasy”, at a certain point, Sophie meets a character who exists in all the stories of women who have perhaps suffered violence. That character is Cleo, who symbolizes the arrival of transfeminism. The story can be different, you can stop feeling guilty, and that’s what the school should teach. Now, at the moment, transfeminism teaches that.

Being a woman is linked to the idea of temptation and then sin, if we want to see it in a religious way, especially. What do you do when people make you feel guilty for who you are? Just for who you are? It’s not always easy to fight that feeling, especially maybe because we belong to Catholic countries and societies.

CJ: Getting away from that guilt is not a straight line, I think it’s probably a lifelong struggle for a lot of people. But I think that just having the conversation to begin with is the best step. And then, after a certain point, I think a lot of it is ingrained, but maybe now people can’t make you feel it anyway because you start to recognize that this is actually a fairly useless emotion.

C: I come from a non-Catholic family, so basically the sense of guilt is not built inside me from the outside, but connected to the outer world. I started to feel the sense of guilt in myself. I don’t like it, as a feeling, I don’t think it belongs to me. So, every time someone says to me, “It’s your fault because you acted like a slutty person”, I become that slutty person, and as soon as I become that slutty person, I realize that there’s nothing wrong with me. So, I experience the worst, what they think is the worst, to realize that it’s not that bad, actually.

Freedom comes in many ways, and freedom is also privilege. I can experience that because my family is not from a fundamentalist Catholic background, I’ve always been quite free to experience sexuality and many things the world can offer to a woman. But I think it’s important to show no fear to the other. You can be an example, like if nothing can move me, nothing can destroy me. They say I’m a beast and a slut and all of that, but it doesn’t affect me at all.

CJ: You said, “it doesn’t belong to me”: it’s such a good word, that’s what it is. I love that.

C: Yeah, it doesn’t belong to me at all. So far, I can pretend sometimes, I try and pretend, I think, “Let’s imagine this sense of guilt”. But I can’t, it doesn’t belong to me. It’s a privilege.

“It doesn’t belong to me”

Sophie says that beauty is dangerous, that the one of women attracts darkness, that IT IS darkness. What is the beauty of darkness for you?

CJ: I think it’s exactly what you were just saying, which is that the implication that darkness is something bad is wrong, I just don’t think it has to be. I think there’s always a different perspective on things, and also, we can really be any way we want to be without taking on the judgment value of “bad” from someone else. If you’re not harming somebody, then nothing you’re doing is bad. There’s no inherent bad except for unkindness and violence and cruelty, so, anything else is just living.

And since you’re talking about “bad”, Ben and Sophie have a discussion about what is considered good and evil. Where do you usually find your goodness? How do you remind yourself that there is something good in the world?

CJ: Dogs. All my dogs [laughs]

C: Where do I find goodness? In sisterhood, and unattended kindness from strangers.

Did writing Maeve and American Rapture helped you shaping you way of seeing religion?

CJ: I think that if you spend enough time looking at anything, you’re going to fall in love with it to some degree. I personally do not love a lot of what exists in the Catholic Church, but I think the good parts of it bring a lot of people a lot of comfort and joy, and I think that’s beautiful. Also, I have come to realize I really love the ritual. Catholics are pretty gothic. It’s dark, it’s very ritualistic, it’s very sensory. So, all of that has probably shaped me in a lot of ways, aesthetically.

“Where do I find goodness?”

Carotta, in “Memoria delle mie puttane allegre” you say, “The ability to redeem yourself, to accept your own limits, to create authentic and deep bonds, to live the reality, abandoning the world of the occult and the divination, becomes essential for the purposes of survival”. This is very closely linked to all this, it also relates to “American Ecstasy”. Can you put into practice this ability to redeem yourself every day? To accept your limits?

C: No! I often cry in a fetal position. I often think I can do better. I often think of myself as a robot.

I’m an only child and that’s quite difficult because I never grew up with someone to confront to or talk to. So, sometimes it’s helpful for me to talk with other friends or families, basically, to remind me that I’m human and I can fail. And I need a good fight. I learned what a good fight was when I was in my thirties. That’s basically what siblings do, and I learned it really late in the years. But that’s what I do when I feel more human.

The ability to forgive is linked to the ability to make mistakes, of experiencing sins in a safe way for oneself and others. This book is about growing up also while navigating through forgiveness, loss, love, belief and changing. What’s the last thing you both discovered about yourselves maybe even thanks to the books you write and read?

CJ: I think I haven’t let myself feel a lot of anger in my life. But with these two books, I have. So, I think any part of ourselves we think we don’t have, most likely is there and wants to come out, and hopefully comes out in a productive way.

C: It’s the opposite for me [laughs]. I’ve been really angry for a long, long time. And I understood that I am forgiving, I can forgive people, and it was good, it’s a possibility, I can do that.

Cleo asks Sophie what frightens her the most and Sophie gives an answer both deeply human and influenced by the way she grew up. Cleo then reminds her that the moments where her thoughts are just hers, those are the moments of true freedom. What’s freedom for you and what makes you feel free?

C: This is the essential question! [laughs]

CJ: That was the last thing I put in the book, that was at the very end, and I’ve worked on this book for about a decade, so it took me 10 years to be able to say that. And I think freedom for me now might just be the ability to write a book like this in a time when I get to speak a truth.

You also said that the end of the world could be a new beginning. What hopes do you both have for the future?

CJ: So many.

We need them! We probably aren’t in a worldwide situation that is very hopeful, but it’s probably also the moment when we need them the most.

CJ: I think it’s so cliché, but compassion for all viewpoints and listening. I think if we can find a shared humanity, we might be able to forget a lot of these perceived differences.

C: I think that people are really scared. I understood that my life was changing because I wasn’t scared anymore. I saw improvement in people around me a lot, when I realized that they weren’t scared anymore of being who they are, expressing what they feel. I think that I wish for everyone not to feel scared of expressing themselves. Nowadays it’s really hard because of political superstructure and stuff like that. In Italy it’s really difficult belonging to an LGBTQ+ community and saying it out loud or being anti-fascist or pro-Palestinian. So, it’s quite hard to express who you are, you know, police will harm you probably. I hope that we will learn from history that where we are going is bad, nothing good happens. We need a democracy where no one is scared to express who they are.

What are you reading right now?

CJ: There’s an author, Seanan McGuire, who’s written like 60 books, no joke. There’s a series called “Every Heart a Doorway”, a fantasy series, I think they’re so beautiful, and I just bought one in the airport.

C: Michael Bible’s new book, “Goodbye Hotel”. He’s a really good writer. He reminds me of Carver’s books, where everything scares you, but it’s reality.

Last question. What’s your happy place?

CJ: For me, outdoors. The mountains and the desert.

C: The place where I was born and raised: Marina di Castagneto Carducci.

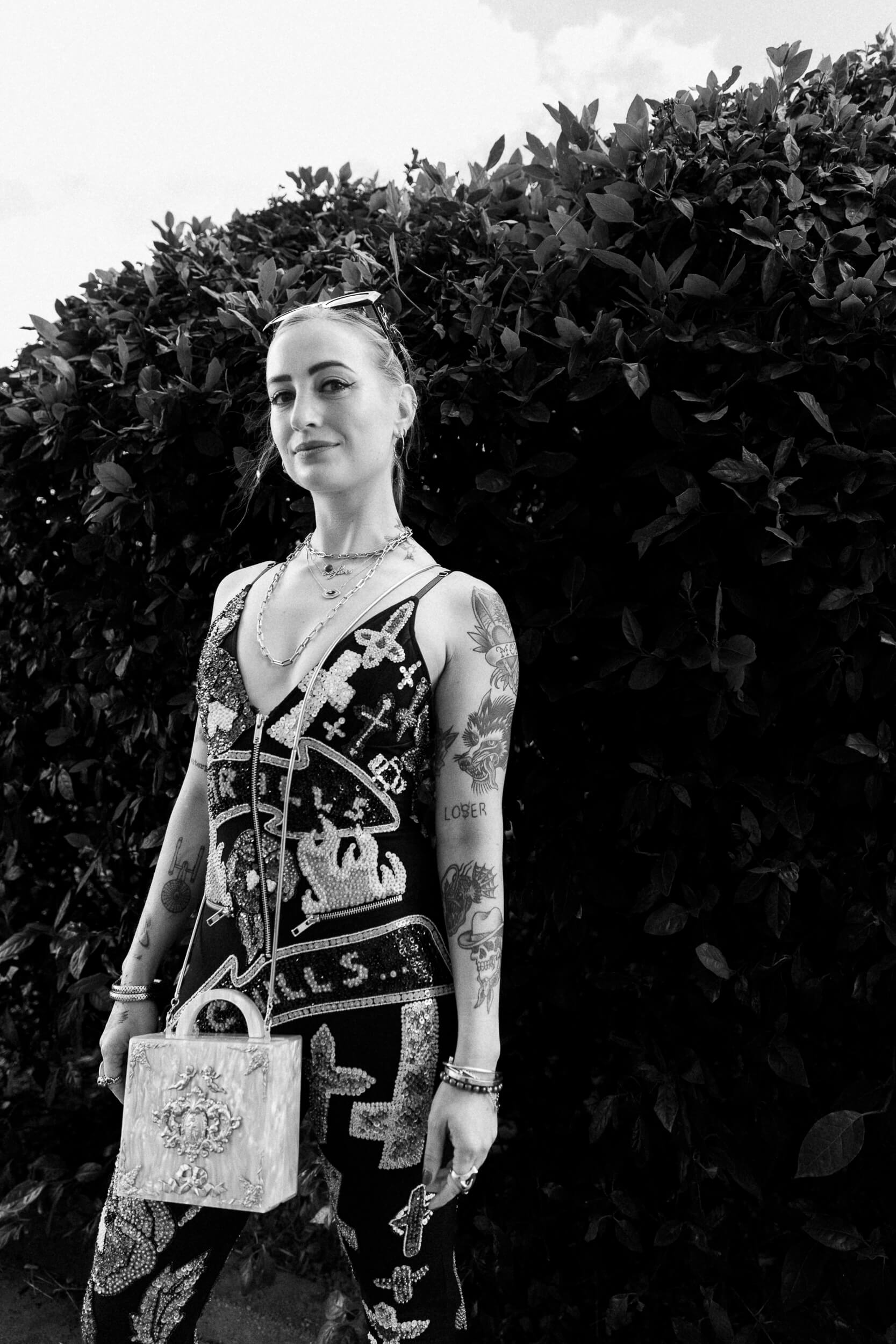

Photos by Luca Ortolani.

Thanks to Mercurio.