Some projects are born from careful planning. Others take shape through chance encounters, instinctive attractions, and emotional urgencies. “L’Integrale”, published by Iperborea, belongs to the latter. It’s an independent magazine, born in 2020 thanks also to the support of Davide Longoni, that doesn’t simply talk about food, but uses it as a deep probe, a narrative device to reach something else: the stories of people, the contradictions of contemporary society, the imperfect beauty of being human.

We sat down with Diletta Sereni, the mind and heart behind this editorial project to hear not just how it began—but, more importantly, why. Why, today, it’s so urgent to talk about food without falling into the clichés of expert gastronomy. Why choose the kitchen as a lens to explore masculinity, vulnerability, power, and transformation. What emerged was a conversation that became a small journey: from disappeared editorial offices and creative friendships, to repressed anger in professional kitchens and tears shed in private; from dishes that unite to metaphors that divide. A dialogue that touches on the tenderness of male identity, the gentle strength of fragility, the linguistic weight of words, and the awareness that food, like all living things, is fleeting. And that’s precisely what makes it so powerful.

In a world that constantly pushes us to perform, simplify, and only show what “works,” there is something liberating in reclaiming our uncertainties—and in cooking a dish that, even if destined to vanish, still tells the story of who we are. “L’Integrale” does this with grace, intelligence, and a rare sense of irony. And perhaps that, today, is the most radical act of all.

Let’s start by taking a step back: can you tell us your story and how you came to realize you wanted to talk about the contemporary world through food with “L’Integrale”?

I ended up writing about food half by chance and half out of a genuine attraction to the subject, but it’s not like I had any particular background—I studied something completely different. The editorial staff of Munchies Italia, which was Vice’s food outlet, launched around the time I started writing about food, so it was a coincidence: I began writing for them, and then I met people I really clicked with, people who were also writing about food. From these connections came the desire to create something together and to explore the topic of food in a way that wasn’t narrowly specialized. Very often food is treated as a subject only for enthusiasts and experts; we wanted to explore it instead as broader, multifaceted narrative material—to use it to tell human stories.

Food is “only” the starting point in this project, a way to delve into human nature and, specifically, the dynamics and stories that make it so rich and nuanced, especially today. What does food mean to you—both in itself and as a universal means of communication?

Food is a kind of probe, a way to get into people’s lives. It’s something we have to deal with daily—at least three times a day (laughs). It’s tied to our lives, our memories, our emotional and intimate selves… But it also involves a collective, political, economic, and cultural dimension. This is the premise of L’Integrale: treating food as a tool to read the world—both on a small and large scale.

The new issue, “L’integrale maschio”, explores masculinity within food culture. How did this theme come about, and how did the issue develop over time?

This one came about differently than the others, born from a kind of frustration in seeing all these events and newspaper sections about “women in food,” “women in wine,” “women in cinema”… It felt like a ghettoization of female representation in these fields. So, among friends and colleagues, we decided to try flipping the narrative—or at least shift the perspective—and put men under the lens. And it felt like the right time to do it, since there’s an important collective conversation happening around masculinity, about how it needs to be rethought—how that’s both necessary and useful. We came up with the idea about a year and a half ago, and the conversation, if anything, is even more alive today. So yes, we started with the theme and then went about populating it with contributors and topics.

“This is the premise of L’Integrale: treating food as a tool to read the world—both on a small and large scale.”

How do you manage the choral nature of inspirations, contributors, people, and facts within a single project? Was there a topic in this issue that particularly struck or surprised you?

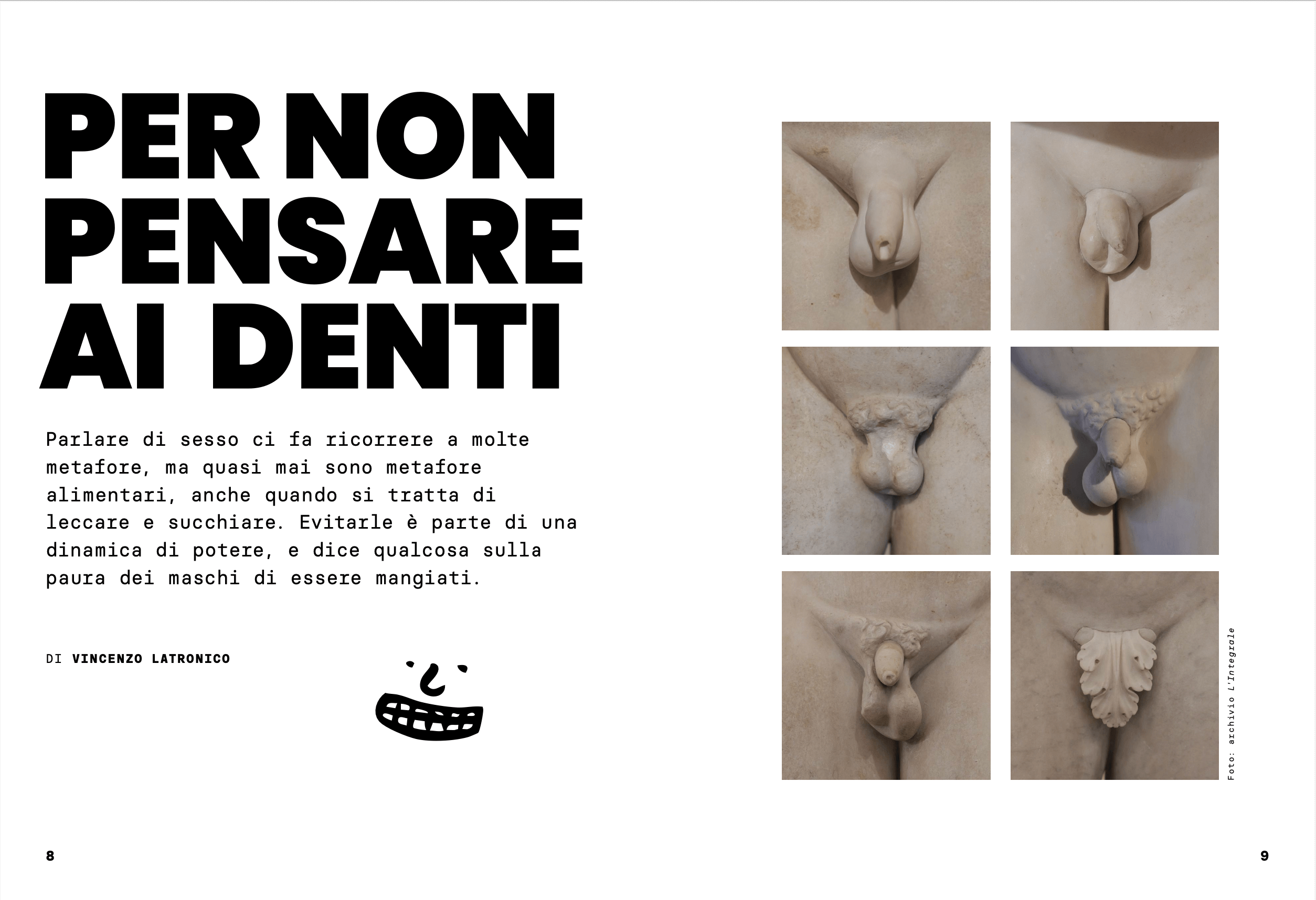

Aside from the humorous beginning, the process of building this issue was the same as the others. This time, it started with a pitch from Vincenzo Latronico, while one of the last contributions came from Martina Merletti. These are two pieces I’m especially proud of because they push the food connection to the extreme: Latronico’s piece explores the lexicon of sex, specifically how oral sex tends to avoid food metaphors even though it involves the mouth and gestures similar to eating. Merletti’s piece is also about metaphors—those historically used by (mostly male) scientists in botany, which are often sexualized or based on reproductive organs. These metaphors are at best arbitrary, if not outright misleading, and she deconstructs them.

In the introduction, there’s talk about being male but also fragile—and how this often results in feelings of fear and vulnerability. In a society where emotional expression is becoming more valued and where mental health is more openly discussed, how do you think people can embrace their fragility and turn it into a strength—perhaps even through cooking?

In general, I think we need to reclaim our insecurities—our vulnerability and anxiety, too. All those soft traits are often seen as flaws or weaknesses. Charlotte Gainsbourg, for example, has said this in interviews: she says she learned to love her anxiety because when she’s uncomfortable, she feels like she’s in a space of discovery and transformation. Unfortunately, no male role models come to mind that are comparable—though they exist, and there will be more and more of them. But for sure, male fragility is less forgiven than female fragility. That’s sort of the premise behind all our pieces: men aren’t forgiven for being fragile, in any form, and this has a ripple effect that leads to a lot of negative consequences.

Then I think of something else, from a different angle, that Tommaso Melilli wrote in his essay for L’Integrale maschio—an essay about the anger that circulates in restaurant kitchens, especially anger expressed by men, who often see it as the only acceptable emotion because they’re ashamed to cry. To me, anger also seems like a way to give yourself importance. At one point, Melilli focuses on a particular moment: that magical time after service ends, when the tension is released and the team stays together at the restaurant, finally without stress and pressure. At that moment, the food that was so painstakingly prepared still exists, briefly, in the bodies of the people who ate it—but only for a little while, because in a few hours it will literally become shit (laughs). So the (creative, human) result of all that stress and effort, in a few hours, is gone. That can be a reminder, or a kind of training, in the idea that everything is transitory. I think that helps you take yourself less seriously—and maybe make peace with your own softness.

“That’s sort of the premise behind all our pieces: men aren’t forgiven for being fragile, in any form, and this has a ripple effect that leads to a lot of negative consequences.”

When reading articles focused on chefs, both professional and amateur, I couldn’t help but think of recent on-screen portrayals—The Bear, above all—where the chef embodies a kind of power and emotionless sensuality, rooted mostly in “primal” feelings. It seems that men are validated more for what they do than what they feel. What social or cultural changes would be needed to validate the person as a whole, with all their contradictions, emotions, and actions?

In The Bear, he gets angry during service because he’s very anxious—but in the end, he’s a chef who cries, even if mostly in private. He’s vulnerable, his emotional complexity is more visible compared to, say, the MasterChef judges who yell and humiliate. Both of these models have contributed to shaping today’s image of the chef. And then, about gender disparities—there are some we don’t often think about. For example, Laura Campiglio notes in her piece that men eat, on average, twice as much meat as women—even though they don’t weigh twice as much and don’t actually need more. This issue gets almost no space in public debate, yet it’s a political topic: it means men’s diets pollute twice as much as women’s.

The exploration of the overlap between sexual and culinary language is fascinating. Do you think we need a better kind of education about this? Words and metaphors have power—they must be used wisely. Can this kind of education happen on social media?

Language education is such a fragmented world that I can only speak to it partially. I feel like it comes only minimally from institutions and much more from informal networks of friendships and from media, including social media. I don’t have much faith in social platforms as sources of education, mainly because of how they’re designed—they’re built to fuel addiction and seek immediate gratification. So I wonder: what kind of content can really come through a structure that operates on those logics?

Another article talks about Gadda’s work and his (tormented) passion for food. Do you have a book, character, film, or series about food that has left a mark on you?

One is Anthony Bourdain, because he significantly changed the idea of what a chef is. He was an explorer doing something that we also try to do, in our small way: using food as an excuse to tell stories about the world and its people. His storytelling—both in books and on TV—was a major source of inspiration. We miss him! Another one is Michael Pollan, who has written many wonderful books about food, showing how the choices we make about what to eat are intertwined with the major issues of our time—environmental, economic, and political.

You dedicate a lot of space to dishes and ingredients, so we’re curious: what are your favorite dish and restaurant?

I’d say eggplant parmigiana, it’s the dish I go for when I need comfort. And then a dish more connected to my roots, which also happens to be the only one I know how to cook: pappa al pomodoro.

What’s something you’ve recently discovered about yourself through your work?

I really hate telling others what to do. Managing and coordinating people just isn’t in my nature—maybe because it’s something I can barely do for myself, so it’s really hard for me to do it with others.

The book, or books, on your nightstand right now?

Because I have trouble sleeping, I always read books I’ve already read and re-read before bed—a new book would wake me up too much. On my nightstand right now for re-reading: a classic, “The Great Gatsby”, which I always keep nearby, and “Sogni e favole” by Emanuele Trevi—wonderful. As for first-time reads, I have a book from Iperborea titled “My Great and Beautiful Hatred” by Elisabeth Åsbrink, and “The Besieged City” by Clarice Lispector.

Last fun question: has anyone ever approached you—or do you know someone—using the line, “I make the best carbonara in the world?”

I feel ancient because I’ve never used dating apps, so this whole carbonara thing was news to me—none of my friends have experienced it either! But my last love story started with discovering natural wines. This guy would take me to drink Georgian wines, wines from the Carso, wines with strange, amber colors—wines I’d never heard of (also because I wasn’t that into wine). It was the first time I stopped to experience that range of weird flavors and aromas that I didn’t even associate with wine. So, no to carbonara—but yes to wine (laughs).

Thanks to Iperborea