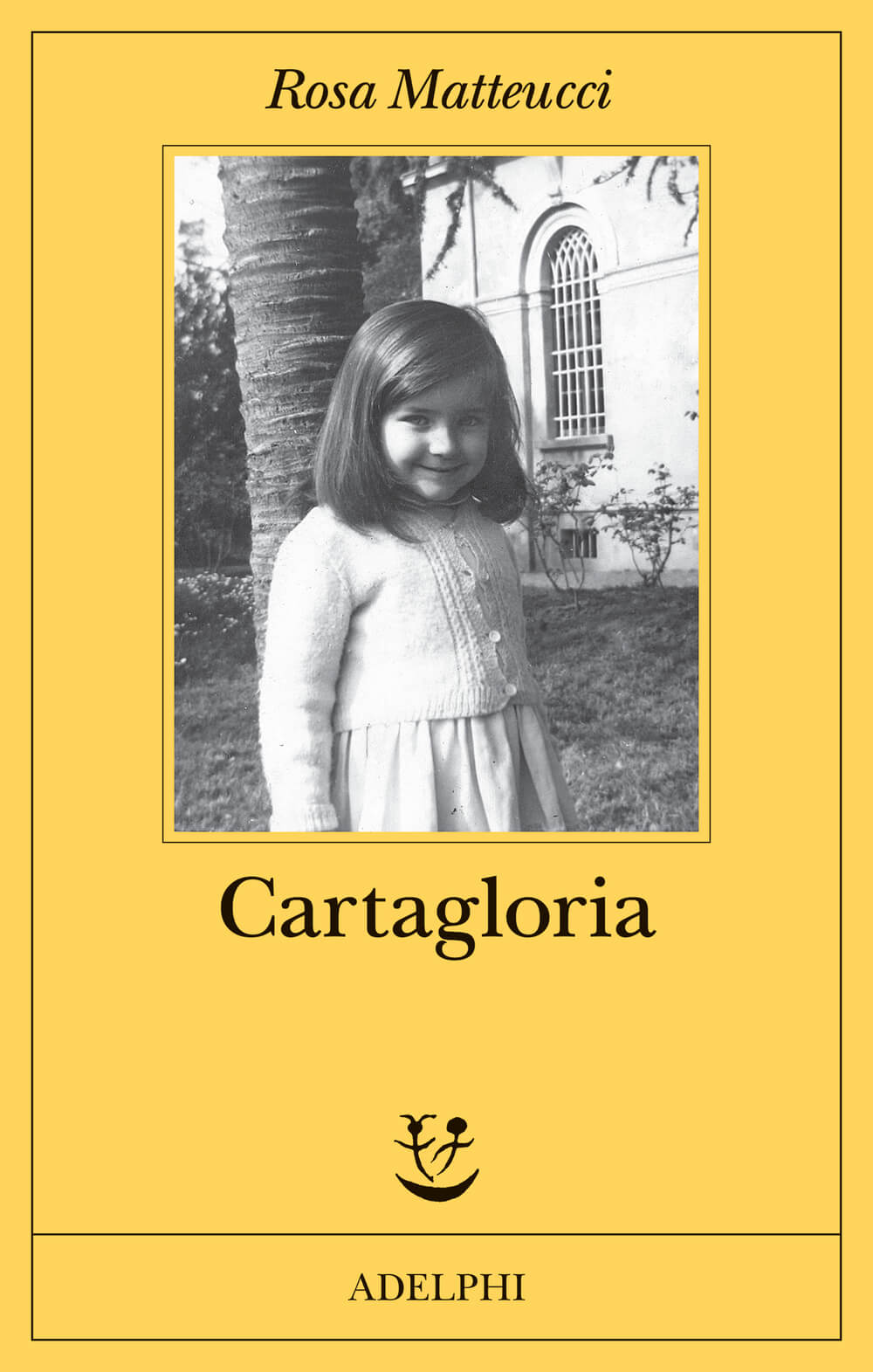

Meeting Rosa Matteucci was not simply a conversation about a book—it was crossing the threshold into a dense, layered inner world, steeped in pain, irony, and grace. Her “Cartagloria”, published by Adelphi and presented at this year’s Turin International Book Fair, is far more than a novel: it is a liturgical act, a disheveled yet powerful prayer, a reckoning with life and with oneself. Within its pages, one feels the weight of memory, but also the fierce desire to redeem it through writing—writing that, for Rosa, is never an academic exercise or intellectual play, but a vital gesture, a necessary act.

This interview was born from a spirit of deep listening. Rosa’s words, like the language of her novel, never leave us unmoved: they prod us, push us to look further. Within “Cartagloria” are ghosts and revelations, fathers and mothers, crosses to bear, and long-silenced words finally spoken aloud. But above all, there is the courage to expose oneself, to hide no longer—not even behind literature.

To step into her universe is to accept being touched deeply, with the awareness that freedom may lie precisely in the act of embracing one’s destiny.

What was your first encounter with a book like?

I learned to read and write late, so my mother used to read to me what she was reading herself. My first memory is of my mother reading Rainer Maria Rilke’s poems in German, then translating them into Italian for me.

“Cartagloria” is a journey through life with all its ingredients: fantasies, dreams, expectations, hopes, false hopes, stubbornness, accidents, miracles. How much of your own experience is in this novel?

Everything is in it—I hardly invent anything. Everything I write has actually happened to me.

Writing is a pleasure, but often also a need or a form of therapy. What sparked the need to write “Cartagloria,” and how did this need evolve during the writing process?

I wrote it because I didn’t want my father to have died in vain—I wanted him to live on in literature. Then it became like cherries—one leads to another—and since “Lourdes” was a novel that surprised me in a good way, I kept going. Still, I think there’s an inner process at work: I do ordinary things, and then at some point, a story becomes clear in my mind and I feel like I have to write it. I do it reluctantly, because writing is hard.

One of the aspects I appreciated most about your book is the language: an Italian that doesn’t let us sit comfortably, that demands our attention—a language that’s certainly complex, but evocative and vividly visual. I’m thinking of expressions like “martial step” or “Host marinated in the casket of the mouth.” I admire a book that teaches me something linguistically, that holds 100% of my attention, and that leaves me enriched after the final page. Based on this reflection, what do you think of today’s literary scene?

More than the literary scene, what I really think about is what the Italian language has been reduced to. The average vocabulary used by young people and adults has shrunk to about 250 words, which is terrifying. The language has been impoverished—Italian is such a refined, beautiful language, with a word for everything, and I didn’t use a single anglicism. I use Italian. In recent years, the Italian language has suffered a series of violations, even sanctioned by the Accademia della Crusca; I was puzzled, but I kept writing in Italian—I don’t care if they make those changes. What I’ve noticed is that readers tell me, “It’s so nice to finally read in proper Italian,” and that makes me happy.

During the protagonist’s spiritual journey, it’s as if the characters in each stage are varying manifestations of a test—rites of passage toward achieving a full awareness of the Self in the world. Is that the true thread of the story? Do you believe that the “characters” in our lives are all “tools” for understanding something greater?

That’s a perfect reading—even though I wasn’t aware of it while writing. And absolutely yes: the characters in our lives are tools for understanding something greater.

The “skits” about the commander-father and the protagonist as his helper are wonderful and disorienting: Jack London’s The Star Rover was the first thing that came to mind while reading those parts, with its tales of reincarnation starting from a present place of imprisonment. Who are your literary influences—those who shaped you and still inspire you?

Consciously, I don’t have sources of inspiration. But there are writers who meant a lot to me because I used to read them. I know Émile Zola’s entire cycle very well—when I was younger, only a few of his books had been translated into Italian, so I read them in French. In some ways, he definitely shaped me in realism, in the attention to detail.

Among the central themes of the novel are feelings of inadequacy, non-belonging, and solitude, all stemming from “absent” and unloving parents. If you could say something right now to your protagonist at the different stages of her life, what would you tell her?

That all these years, no one ever really saw you. But now, so many people finally do. I need to be seen.

What is your relationship with solitude today? Do you seek it or fear it?

I definitely need at least two and a half hours alone every day. I know solitude well—I’ve been alone for many years, so it doesn’t scare me much. But a lack of contact with others can dry you out; so even if you don’t feel like talking or socializing, for your well-being, sometimes you have to make the effort.

So how does one find their place in the world—the “tribe that welcomes us”? Have you found yours?

The moment I accept to carry my cross, I accept my destiny—from that moment on, I’m free. It was a long and difficult search, but now I feel free.

The book on your nightstand right now.

There are quite a few because I read or reread many things at once. Right now there’s “L’Assommoir” by Émile Zola—I practically know it by heart. Then there’s one by Michael Bible, and an essay by historian Marco Patricelli about the king and Badoglio fleeing Rome in 1943. And definitely “The Notebook Trilogy” by Ágota Kristóf.

Is there anything new you discovered about yourself during or after writing the novel?

I discovered that for many years I thought I was ugly compared to my mother—but I never actually was.

What does it mean for you to feel comfortable in your own skin?

Being at peace with myself.

And what is your happy place?

I don’t think it exists, because we’re always at the mercy of external forces.

Final question: what do you recommend we read?

“Don Quixote” by Miguel de Cervantes.

Thanks to Adelphi Edizioni