There are actors who come to cinema out of desire, and others who come to it out of necessity. Matteo Santorum belongs to the latter category. His story begins far away, in a childhood made up of imagination, silence, and invented stories to fill spaces – both physical and emotional – and arrives at a vision of art as a place of care, responsibility, and relationship with the other.

In our conversation, Matteo moves freely and without filters through the themes that define him: the almost physical need to act, the political and emotional value of representation, empathy as a revolutionary act, the courage to inhabit fragile, dark, uncomfortable characters. From the comedy “L’appartamento Sold Out” to the disturbing theatre of “In casa con Claude 2.0”, what emerges is the portrait of an actor who seeks neither refuge nor complacency, but an authentic dialogue with the present.

With Matteo we spoke about cinema and theatre, yes, but above all about identity, love, wounds, and that deep necessity to tell stories in order to feel – and help others feel – a little less alone.

What is your first memory connected to cinema?

I come from a small town in Trentino, and I remember that once, when I was four or five years old, my grandfather took me to see a restored version of Walt Disney’s “Snow White”. Another memory is more connected to popular national TV, namely Totò. Every time I went to my grandfather’s house, I would spend the afternoon glued to the TV watching Totò with him.

I grew up in a house where there actually wasn’t a TV, so my desire to act was born from a need to explore stories and worlds, to escape, to find a place of my own.

Was there a specific moment when you realized that acting for you was not just a desire, but a necessity?

For me it’s really something prenatal, because ever since I was a child I’ve loved entertaining. I liked telling stories: my parents run a historic trattoria in Trentino, and when my mother couldn’t look after me because she was a teacher, I would sit at the counter with my father and grandfather. Every now and then I’d slip out of their sight and go tell stories to the customers. I was four years old! Or I’d climb trees imagining myself as certain characters – I was obsessed with Zorro and Robin Hood.

You know, I spent a lot of time alone because my parents were working, rightly so, and I liked dressing up and playing characters. I was an only child until I was four, so I felt very lonely as a little kid, and that was my pastime. My brother, however, is extremely different from me – very calm – while I was quite demanding, tearing the house apart and creating my own stories, my own worlds.

So acting was born in me as an almost animal, physical, nourishing need. I often say it: acting gives me a place in the world, it gives meaning to my existence. I have a degree in literature, for example, but purely out of personal passion – I never thought of a professional path in that field. I don’t have plan Bs: acting heals me. And I think it can do the same for others.

It’s one of the highest purposes of art, to heal, right?

“I don’t have plans B: acting heals me.”

I think so too – we often forget that.We tend to underestimate the importance of the role art plays in our lives. It’s medicine, or at least complementary to medicine.

You’ve stolen my words. In this life I’ve devoted myself to my love and passion for acting, but an artist must always look for a “why”, right? What an artist does isn’t motivated solely by the need to be seen because they were abandoned; we all have our traumas. But when I ask myself why I do what I do, my answer is the idea of being able to tell stories with emotional weight and human meaning – stories that can truly offer help, support, and change something in the public imagination, to plant a seed. For me, that’s one of the greatest victories when it happens, more than recognition, which of course is good for the ego. But I think we focus too much on entertainment for its own sake.

One of my favorite directors, Luca Guadagnino, once said in on Italian talk show that art is sometimes uncomfortable, because it has to remind us of things, make us reflect, dig inside us and force us to think about parts of ourselves we don’t want to think about.

True art touches our most delicate buttons. It pokes at our weak points, and if we’re not willing to face and process them, we run away from that art. Speaking of art and one of your latest projects, “L’appartamento Sold Out”: you play Lorenzo, a character who finds himself in a rather unpredictable living situation. What attracted you to the emotional and human chaos that defines his story?

Lorenzo is the next-door neighbor of the apartment’s tenants, the one who tries to establish some balance while making a big mess. What struck me about this project is that, even though I love socially engaged art, I realized there’s also a need for a kind of art and communication that, perhaps in a lighter way, sheds light on themes connected to what’s happening in Italy today, using a language that’s more accessible to everyone.

I think shifting our gaze from ourselves to the other is the key to any kind of coexistence – from roommates to parents. Many family relationships don’t work because a parent is a victim of their own personal story and projects that gaze onto their child, blind to their needs and who they truly are. What “L’appartamento” teaches me is that with every person a different kind of dialogue is born, because everyone we face is a different human being, unique precisely for that reason. We must start from them and then arrive at ourselves for a relationship to work in a balanced way.

Lorenzo is a pansexual character, which unfortunately is still an exception in Italy. But telling these stories with a lighter language allows us not to problematize something that shouldn’t be problematic – like homosexuality – rather than portraying it only as something “difficult,” and instead imagining a love that simply works, smoothly. You know what I mean?

“Everyone we face is a different human being, unique precisely for that reason. We must start from them and then arrive at ourselves for a relationship to work in a balanced way.”

Absolutely. Forcing the narrative of same-sex love as “normal” often makes it feel even more “different.”

Exactly. Seeing these kinds of stories on screen also gives you a sense of existing – you think, “Okay, I exist too. There’s a story that tells me, something I can relate to.” And that’s powerful, because it does you justice, because it’s not a cliché, because it has its own emotional truth and strength. As an actor, if you reach even one person – and that person might be a teenager full of questions – that’s a huge victory. Director Francesco Apolloni was very smart in choosing comedy as the language, because it embraces everyone.

And it’s easier to watch even when you’re mentally tired.

Exactly. After work you think, “I want to watch something light,” but somehow, unconsciously, that light thing is doing a lot to you.

Another of your projects has nothing to do with comedy: the stage play “In casa con Claude 2.0”. There you play a very dark, layered character. How did you enter his mind without judging him?

I’ll give you an example: I aspire to play the great dictators of history. These personalities are born from immense fragility – they have a very significant shadow side, and they invest others with it, dragging not only themselves but everyone around them into an abyss. It makes me think about how we humans aren’t born with this darkness. I’m convinced we’re born pure: child soldiers in Vietnam aren’t born wanting to kill so lightly. It’s about how you’re educated, or how society shapes you.

I come from a privileged background, despite having deep wounds, but art saved me – it gave me a purpose and spared me other scenarios. Still, it was a choice I made, thanks to the tools given to me by those around me, the encounters I chose to follow, the trust I decided to place. The same goes for my character. Unfortunately, he didn’t have the strength or the tools, and he wasn’t born into the right context. So he chooses a certain kind of story rather than another, requiring different human efforts that lead him into a great dark space, dragging along the love of his life. He isn’t even aware of what he’s doing; post-traumatic stress causes him a schizophrenic, extreme behavior. That’s why Yves believes he’s saving his lover’s life – because a love like that, in a twentieth-century city, cannot exist.

He also never had parents who could love him, so he doesn’t even know what love is. That’s how I approach characters with such deep shadows: starting from the idea that we’re born fragile beings. I relate to the character as a fragile being whose fragility was not healed or valued, but crushed – as often happens.

Think of how men were idealized in the past: strong, therefore insensitive. If you teach someone that crying is wrong, they’ll never feel empathy.My character made choices that distance him from me, born of severe trauma. I fight every day so that my own traumas don’t harm others – that’s why I first went to therapy. I didn’t want to hurt the people close to me. So, I tried to dialogue with Yves, asking where his actions come from, what crack allowed that shadow to seep in – something I must not judge. That’s how I entered his soul.

“That’s how I approach characters with such deep shadows: starting from the idea that we’re born fragile beings”

How do you think today’s audience receives this story, an updated version of a very powerful older text?

Society should have made progress when it comes to the kind of love being portrayed. The language has changed, but the text remains necessary as long as gay teenagers take their own lives, or women are killed by men who say they “love them too much”. The story still mirrors the present, unfortunately, despite being set in the ’70s and ’80s. We’ve taken many steps forward, and many steps back – perhaps because being well scares us, and so does dialoguing with something that reflects us and questions us.

We live in a time where identification is needed to assert ourselves, but if we learned to accept ourselves, we wouldn’t need labels. The truth is we must fall in love with the human being as they are, beyond everything. Shifting our gaze from ourselves to the other, we leave behind the suffering and oppression of our personal stories and forget what society told us was right or wrong.

What’s the last thing you discovered about yourself through your work?

I’m understanding what would happen if we allowed ourselves to be truly human – without superstructures, without masks – if we let ourselves return a little to being children. As Pasolini said, a child can always teach us something. Children laugh when they need to laugh, cry when they need to cry. As we grow up, we’re taught when not to laugh, when not to cry. I’m not saying we should descend into incivility…

Otherwise we become animals.

Exactly. But if we dropped the mask and allowed ourselves to show who we really are, I think we wouldn’t be discussing all these issues, and many things wouldn’t happen. We’d be far more empathetic. My work is teaching me how empathetic I am – sometimes too much. My slightly melancholic temperament makes me turn everything into a personal burden, including what’s happening in the world.

But empathy is the key. If we were all “better actors”, in the sense of questioning ourselves, dropping the mask, and seeking empathy, we wouldn’t be indifferent to children dying, for example. Much of it is due to the armour we’re taught to wear, especially men. As cliché as it sounds, it’s a fact that women are often less indifferent, because they’re allowed to cultivate that fragile, empathetic side – men aren’t.

What do you look for in a character or a project?

I say no to things that don’t represent me, that are far from why I want to make art. I choose projects I deeply believe in and that help me grow artistically. My dream is to find a project – a TV series, a play, a film – that has clear human values and takes a stand on historical realities. Many people ask why we keep making films about World War II. Unfortunately, we need them – historia magistra vitae. I want to do something that contributes to dialogue, that allows me to take an artistic and human position on an issue and uphold values that clearly support the human being. That’s why I mentioned Luca Guadagnino – he does this in all his projects. Think of “After the Hunt”, “Bones and All”. I also love Valeria Bruni Tedeschi for how she portrays humanity. I want to channel everything inside me into a work of art. That’s also why I started my own small production company – I’m producing short films with artists I love.

What makes you feel truly safe? And what makes you feel confident?

I’m very stubborn and very insecure at the same time. When I finish a theatre show, I always think I did terribly – until the audience comes to compliment me, asking how I manage to hold their attention the whole time. Maybe my stubbornness and the light I’ve carried since childhood convince me I’ll get where I want, that nothing can stop me.

What makes me feel safe is surrounding myself with affection. Unfortunately, I struggle to be alone.

Unfortunately? I’d say fortunately!

Yes, but sometimes that need has its downsides.

Because it’s hard to find the right people.

Exactly. I want a few people by my side, but good ones – who can become my family, my team. They make me feel safe. Family isn’t just the traditional one; as you grow up, you realize family also includes those you meet along life’s path.

I believe we all have a purpose. If we’re here just to fill our days, what’s the point? We could disappear overnight. I want people beside me who live with purpose and who demand that I do too – reminding me of my direction and keeping me company on this journey.

“I want people beside me who live with purpose and who demand that I do too”

Your greatest act of rebellion?

Being an actor – it’s a constant act of rebellion. I love my land and its nature, but I come from a small town where, historically, acting isn’t seen as a real possibility. My rebellion – toward society and myself – is telling myself: you’re 25, you’ve already done what you had to do. What you did, you did because it had to be so; what you didn’t do, also because it had to be so. Breaking free from the anxiety imposed by social expectations about reaching certain milestones by a certain age – that’s my rebellion.

Your greatest fear?

Not making it. Not being able to live off my work. Failing. But I’m very spiritual, so I believe everything is part of a design. If I have this fire burning inside me, there’s a reason.

I’ll share something my mother told me for the first time: “I’m happy when I see you happy.” My first thought was that to make her happy, she has to see me at the premiere of my life’s film. When I was little, she bought a red tulle skirt and I told her, “You have to wear it when I win the Oscar” [laughs]. My mother was my first supporter. She knows I pour everything into this work, driven by a social and emotional urgency to change things and help others. I want to succeed at that.

What does it mean for you to feel comfortable in your own skin?

I struggle with it. Sometimes I fight with my image, because we live in a society that imposes certain standards. So how do we do it? Maybe by recognizing and valuing our uniqueness and that of others. Only then can we feel at ease with ourselves, because we admit that it’s okay as it is. Do we really want to be a standardized product? If we’re in the world with this body, this voice, once again, I think there’s a reason.

What is your happy place?

The first image that comes to mind is poetic: returning to being a child who plays and creates without thinking whether it’s right or wrong – just immersing himself in his world because that’s what he wants, without answering a thousand questions. My happy place is the treehouse I forced my father to build for me as a child [laughs], where I could hide, create stories, escape. I’d also say my brother – he’s a man I deeply respect, he’s my home, the closest thing to me; and my work, when it’s done with people who put heart into it, not just money.

I’m constantly searching for this happy island, because I think it’s always reshaping and redefining itself. There’s a poem by Kavafis called “Ithaca” that says something beautiful: we live waiting to find this happy island, the destination, but we forget everything else. In truth, the happy island in daily life is a compass pointing us toward where we want to go, but it’s also constantly changing. I can’t live waiting for a happy island that has yet to arrive, but I can nourish myself with the desire for an island that, in every phase of my life, I know will make me happy in some way. Kavafis writes, “If you find her poor, Ithaca will not have deceived you”, meaning Ithaca has nothing to give you, because you should have found riches along the way. Of course, we all want an Oscar in our hands [laughs], but what brings tears to the eyes of the actor who wins it is the awareness of what that statue means – knowing what they’ve gone through to get there.

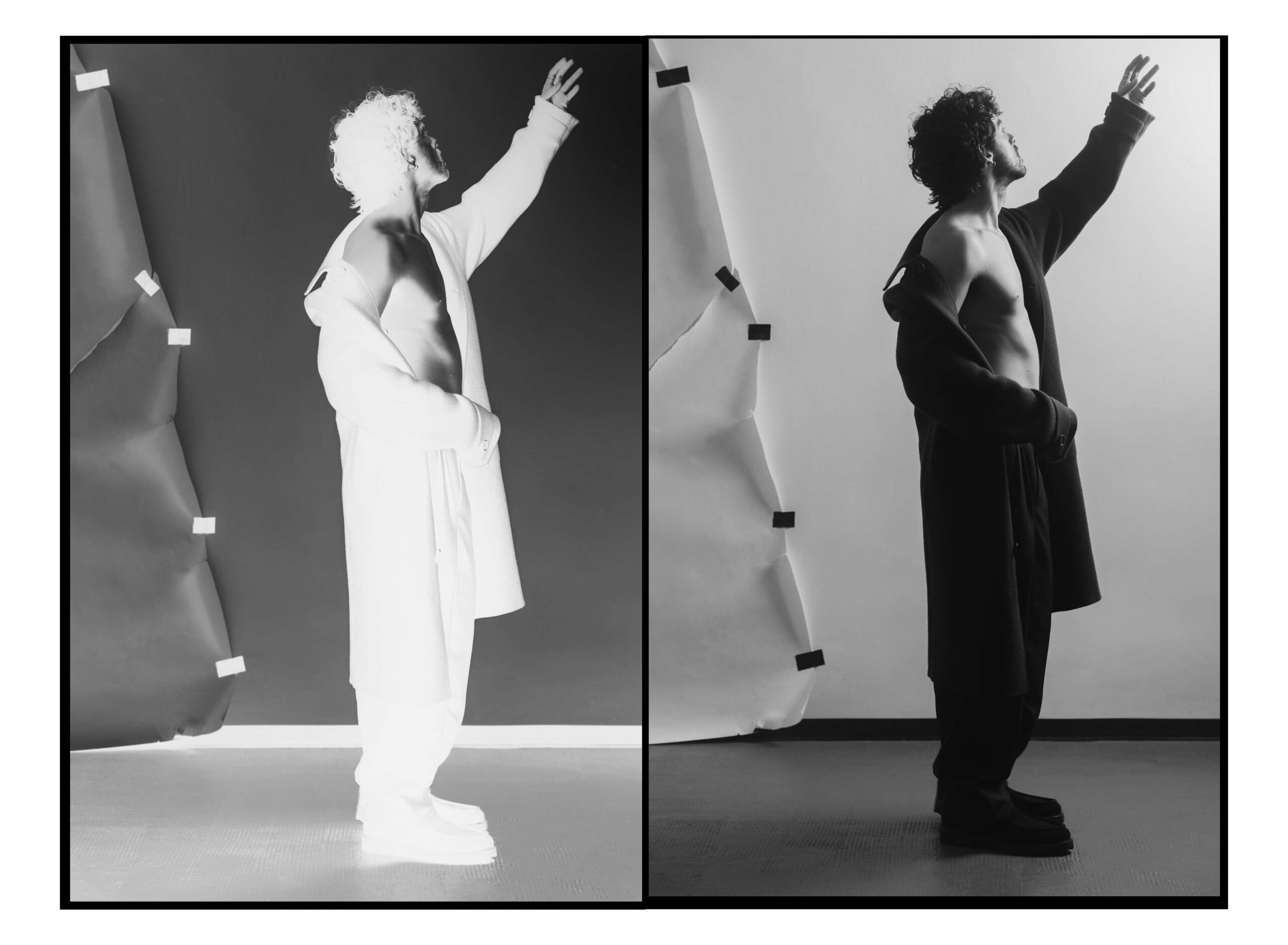

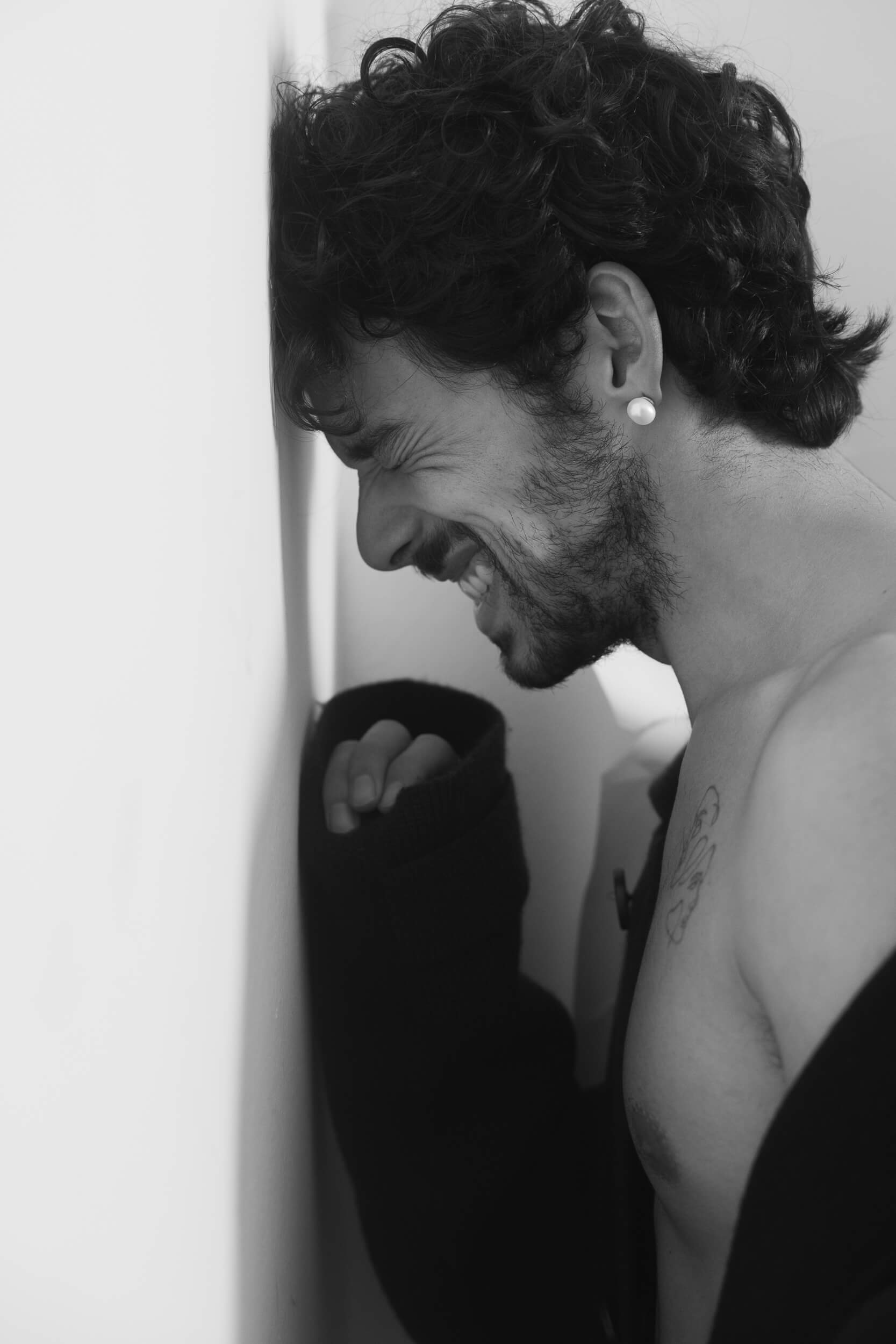

Photos & Video by Johnny Carrano.

Styling by Ilaria Di Gasparro.

Grooming by Sveva Del Campo.

Thanks to Davide Musto.

LOOK 1

Trousers: Pence1979

T-shirt: Nude Project

Blazer: Trussardi

Shoes: Sebago

LOOK 2

Total Look: Iceberg

LOOK 3

Total Look: Brioni