Jared Harris moves effortlessly between worlds — from historical dramas to science fiction epics — always bringing a quiet intensity and a sharp understanding of human complexity. In Kathryn Bigelow’s “A House of Dynamite”, he plays the U.S. Secretary of Defense, a man forced to confront the unthinkable reality of nuclear threat. In “Foundation”, now in its third season, he returns as Hari Seldon, the brilliant mathematician whose vision of the future is as fragile as it is ambitious.

When we met, about a month after the premiere of “A House of Dynamite” at the Venice Film Festival, Jared spoke to me thoughtfully about fear, power, and moral responsibility — both in politics and storytelling. Our chat drifted between the real and the imagined, from Cold War facts to intergalactic empires, revealing to me an actor who approaches every role as a way of understanding what drives us as humans, and what still keeps us awake at night.

What is your first cinema memory?

The first thing that comes to mind is “Jason and the Argonauts”. I was at a boarding school, and the house that I was in was called The Spartans, so, I was already sort of headed towards Greek mythology and all that kind of stuff as a child. I remember I used to watch that film over and over again.

I watched “A House of Dynamite” in Venice, during the Film Festival, and I really liked it, it made me feel so much. Your character, the US Secretary of Defense, is haunted by the fear of nuclear weapons – a fear that’s both collective and deeply personal. How did you work, individually and with the director, to embody that kind of universal anxiety?

Well, I think for my character it begins almost as a kind of suspension of disbelief – an intellectual exercise. He’s aware of the threat of nuclear weapons, of course, but it’s something abstract until it suddenly becomes personal. When he realizes that one of the cities that might be targeted is where his daughter lives, everything changes. The fear stops being theoretical and becomes painfully real.

I also think that, historically, we believed we had “won” the Cold War, and that sense of victory made us complacent. Once the two superpowers made peace, we collectively thought, “Well, that’s over – we don’t need to worry about it anymore.” But, as the film points out, for the first time in decades, we’re actually building more nuclear weapons instead of dismantling them. That fear, that dormant anxiety, has quietly resurfaced – and the people in power, like my character, would be deeply aware of that.

What’s particularly striking is that the idea of a nuclear attack still feels almost unthinkable. Yet we had two military advisors on set – both from STRATCOM – who had spent their entire careers running these very scenarios, day after day. They told us that these exercises used to involve the Secretary of Defense and even the President. But when information started leaking – revealing what choices a president might make – it became too risky, both politically and strategically. In fact, the last president who personally took part in such exercises was Reagan.

So, in a way, what’s terrifying is that the people who would have to make these decisions today – the president, the defense secretary – would be doing it for the first time, in real time, with the world watching. Everyone else, the strategists and advisors, they’ve rehearsed it in theory. But the ones at the top? They’re thrown straight into the fire. And that, to me, is what makes it all so unthinkable.

Yeah, well, I think director Kathryn Bigelow has a way of grounding tension in realism – in physicality, in detail. Was there a moment on set that unsettled you, or made you reflect on how close fiction can get to reality?

There are two things that surprised me: the fact that they only have 50 of these interceptors, and also how difficult it is to intercept those missiles. You have to hit them when they’re orbital and outside of the atmosphere, which was pretty unsettling to find out. After I shot this film, I went to go and shoot a movie called “Reykjavik”, about the summit at Reykjavik to end the Cold War. It had to do with how many ICBMs each country had – medium, long-range, etc. – and the whole negotiation between Reagan and Gorbachev.

So, yeah, I’d considered that. But I also remember, as a kid growing up, the idea of nuclear annihilation was very real. In a way, it’s similar to the anxiety that the young generation has now about the ecological disaster. The anxiety that the young generation feels now about that, my generation felt it about the idea of suddenly waking up one morning and finding ourselves in a full-blown nuclear conflict. So, I didn’t have to reach very far to find that anxiety – it was just in my back pocket throughout my childhood and young adult years.

“I also remember, as a kid growing up, the idea of nuclear annihilation was very real. In a way, it’s similar to the anxiety that the young generation has now about the ecological disaster.”

Did working on this film change the way you think about power, especially the fragility of it, and about individual responsibility in a geopolitical context?

I think what this film made me hopeful was that the right person or the right people were going to be in those positions to make those calls. Because what you realise from watching how this structure works and how the mechanism of decision-making works, is that the human element is the most important element. You know, there are these prescribed steps that they have to follow, but at the end of the day, it’s a human being who’s going to decide, and you want them to make a call that’s based on not just a feeling for their own survival, but for humanity in general. So, it made me appreciate how important it is to have somebody in that position who’s open in that way, if you like.

Some people say that “ignorance can be bliss”. What is your opinion on this? Do you think we all have a duty to confront uncomfortable truths? Or is there value sometimes in not knowing?

I think it depends on what it is that we’re dealing with. I think, in some examples, ignorance might be bliss in the moment that you’re sleepwalking towards disaster, you know? So, it’s important to get your head out of the bliss cloud. You don’t have to stick your face in the toilet bowl the whole time, but you can have a balanced view of it.

Younger people don’t have the same experience of that anxiety about nuclear annihilation, but their feeling is all about the ecological situation, and in situations like that, similar to this one, ignorance is contributing to the problem. But, again, the trouble is we’re not in those rooms to make those decisions, so I guess all we can do is try and impress upon our leaders how important these things are to us, and maybe they’ll focus on that. But also, we have to understand that it’s very difficult for these guys to deal with something that seems like a hypothetical, you know?

I would say, in certain situations where ignorance is bliss, would we want to know the day when our number is up? I don’t know if that would be a great thing. So, in that sense, ignorance is bliss, but in terms of some of the big picture stuff, I think being informed is good.

And was there a specific moment, maybe a scene or a discussion on set, that made you see the subject of nuclear fear or moral responsibility in a new light?

I think it was the determination that Kathryn and Noah Oppenheim, the writer, had about it not being a partisan issue. That’s the reason why there was deliberately no indication or signposts as to which party was the administration power, because at the end, if it happens, it doesn’t really matter which party you are. You’ve still got the same problem you have to deal with, you still have the same decisions to make. At that point, it doesn’t matter – I’d say they were all Americans and they were all human beings. To answer your question, it would have been that discussion because I did bring it up. Actually, I think everybody brought it up at some point in the part of our preparation and study and trying to figure out those little details that were going to help us. Kathryn said there was a specific reason why they did not want to do that: they didn’t want it to get caught up in that, you know, the partisan echo chambers that exist now.

Actually, this film, I think, doesn’t seem to offer any easy answers. It leaves space for doubt, for reflection. What questions would you like the audience to take on after watching it?

Well, I think that’s more or less been teed up by Kathryn and by Noah, and that’s just a general conversation about not going back to getting caught up in a new arms race.

I think films are supposed to be entertaining first and foremost, and then behind that, if they’re powerful, then they stick in your mind for a reason, and that reason is the thing that you ruminate on, which could be different for all sorts of different people – they take out of it what they put into it, so you don’t know what that’s going to be. But in general, I would think it would be questions about the sorts of the future, of what we want to do with this Pandora’s box that we’ve opened and can’t close – you can’t get rid of this information, it’s impossible to not know it any longer. But you want to control it, you know? I’d say definitely don’t hook up all the missile sites to some AI supercomputer because I’ve seen “War Games” and “Terminator” and we all know how that goes. So, let’s keep the human element involved in turning that key always.

Hopefully. And now, changing subject, you also play a key role in a super cool TV show, “Foundation”. Season 3 has recently ended, and I think it felt more “space opera” — bigger, more spectacular. How did that shift affect the way you approached Hari Seldon’s presence and energy on screen?

First of all, this season is more nakedly an action-adventure story, and part of it is that Lou Llobell‘s character, Gaal, spent the first two seasons being defined and then restricted by her relationships with Raych, with Salvor, and with me, and she was sort of having to bounce off of those before she really properly had her own story and her own arc, if you like, or her own mission. With Hari disappearing to wherever he disappeared to, he properly hands over the reins to Gaal. So, she was able to pursue a more exciting, familiar story arc in that sense, and it was a good action-adventure story.

On the other side of the story, we’ve properly got the foretold crumbling of the Empire, and what’s brilliant about it is that it’s destroyed from within, it’s not destroyed from without. I mean, there’s all the pressure from outside that’s slowly been chipping away, but at the end of it, the rush towards the conclusion of it it’s because it crumbles from the inside, and that’s very clever storytelling.

One of David Goyer’s gifts is he’s a good plotter – his mind is naturally gifted towards constructing plots, and as far as I’m concerned, or my character is concerned, I feel like it’s drifting towards irrelevance. Essentially, whatever gifts Hari had, Gaal has them and a superpower, so, it almost makes whatever Hari brings to the table irrelevant. And I think that’s what’s happening on that side of the story for him.

You’ve spoken about being actively involved in shaping some scenes in “Foundation”. How collaborative has the process been between you and the writers when it comes to refining Hari’s voice and arc?

Yeah, that’s always been a dialogue. In the writers’ room, each character has three words, if you like, that define them. So, when you get the scripts for a new season, it’s almost like going back to square one – you look at where you started, and then you have a conversation about how things have changed. I feel like we’ve moved on from those early definitions now.

For example, in this latest season, the idea was that Hari would once again pull a clever, fast one on Gaal – in the story she wakes up to find out that he’d been alive all along, and it is a surprise for both her and the audience. But I said it just didn’t feel believable. Those were her people, and they’d tried to kill him last season. They wouldn’t deceive her like that. The only way it could make sense was if she already knew and had agreed to it. Maybe he could have stayed awake a little longer than they planned, but it would only have worked if both of them realized they didn’t have enough runway, and one of them was going to have to stay awake to get them there. It’s little things like that – the relationship has changed. They trust each other now, they’re working together, and you have to reflect that.

I remember another example from season one, episode six, when Raych kills Hari out of the blue – which was like, “What the hell is going on there?”. I had a conversation with David about it and said, “Even if you think it’s the right thing to do, it doesn’t feel emotionally true”. I told him, imagine taking it out of the science fiction context – say you’re terminally ill and you go to Dignitas in Switzerland to end your life. You don’t hand your son the button and say, “Here, you push it.” And even if you did, it would take a lot of persuasion if you love someone, even if you believe it’s the right thing for them. I just didn’t feel like we were there yet in that scene. So, we wrote another version, where it was clear that Hari was going to kill himself – that it would be suicide. Raych would stay behind to arrange the funeral and then, two weeks later, disappear in the night and go to the Raven to meet Hari there. But then Hari would discover that Raych and Gaal were in love, and he understands human nature well enough to know that Raych wouldn’t go. He would find an excuse to stay, Gaal would get pregnant and he wouldn’t abandon their child. So, the only way Hari can be certain that Raych leaves the ship that night is by making sure that he can’t stay – and the only reason he couldn’t stay is if he’s killed Hari. We actually shot that version of the scene, but they didn’t use it.

“In the writers’ room, each character has three words, if you like, that define them. So, when you get the scripts for a new season, it’s almost like going back to square one”

Speaking of big emotions, what is the latest TV show or movie that you watched and that particularly stayed with you for a while after watching it?

Oh, wow, it’s a good question. You know, I watch a lot of stuff. “Barry” was a fantastic show, well written, incredibly well directed, also, I really liked “Dept. Q” a lot.

And what are you reading right now?

You know, I no longer read for pleasure because I have to read so much for work. I’m reading scripts, loads of them, every week, and doing research. So, I don’t read for pleasure anymore, which is a pity.

I understand, it was the same for me on my last year of Uni. I just read so much academic stuff all the time to prepare my dissertation and last exams that, in my spare time, my eyes just rejected any other kind of “ink on paper”.

Yeah, that’s it. For me, even reading a friend’s script is a massive commitment because if you’re reading a script to see whether you’re interested in it or not, if I’m not captivated by the story by 30 pages, then I stop and think they should find someone for whom this story is meaningful to. But if you’re reading a friend’s script, then you have to help them and give them your thoughts and be considerate, so that can take three or four hours of reading their script.

And what is the latest thing that you discovered about yourself through your work? I guess you actors live so many different lives that you get to know human nature better and better, as well as yourselves.

Yes, you do become a good student of human nature, that’s for sure. What’s the most useful when you’re looking at characters and playing characters and putting that kind of profile together is the things that the characters are not aware of about themselves or in denial of because that’s a very powerful engine. However, that’s a lot harder to do to oneself, you know, it could take decades of therapy. Also, a frightening question to answer in public [laughs].

I know, right?

What would you like to see outside your window, right now and forever?

I love the sea. I like to hear the sound of the sea when I fall asleep and the smell of the sea in the daytime, I find that very relaxing.

And what was your greatest act of rebellion?

You know, because I was the middle kid, I was always a little bit obstreperous. If someone said, “Don’t do something”, I would always immediately do it. So, there’s lots of examples like that when I was a kid. For example, we weren’t allowed to have sweets at school, so me and my best friend had a sweet shop racket, and we would auction off sweets to the boys at school and then we would go around collecting the money they owed us at the end of term. We were like little thugs!

Other than that, I would say my biggest act of rebellion was going to college in America. Actually, that was not so much a rebellion, but rather a sort of striking out for independence and freedom from the expectations of my family about who they thought I was and not being happy with the box that they were trying to put me in. I didn’t really know what I wanted to do or what box I wanted to be in, but I just knew it wasn’t that one.

And what is your biggest fear?

Unemployment. That’s terrifying. I don’t believe in hell, but I believe in unemployment.

So true.

What does feeling comfortable in your own skin mean to you?

That’s a good question. I just remember it was harder to feel that way when you’re younger. I guess it has more to do with just either accepting or being resigned to, “This is who you are. These are the cards you’re dealt. Play the hand you were dealt and stop trying to wish you’d been dealt different cards”. You just start giving yourself a hard time, you have all those thoughts and voices in your head that are constantly barracking at you and criticising you and chipping away at you, second-guessing you all the time in your mind. It’s quieting those voices down, I think.

“This is who you are. These are the cards you’re dealt. Play the hand you were dealt and stop trying to wish you’d been dealt different cards.”

That’s not easy at all, though, becoming louder than the evil, devaluing and manipulating voices in your head.

No, it’s not. You know, I went to a meditation centre for three days in Rochester, New York. There you just spent the whole day meditating. The idea was to see if you could count your breaths up to ten and whether or not you could get to ten breaths without an intrusive thought. It’s really difficult. One of the first things they do is they put a flower in front of you and they say, “Look at the flower and just look at it. Observe the flower. Don’t think of anything, just see how long it takes for your intrusive mind to comment or say something”. It’s within seconds, it’s so difficult to do. But I do remember that at the end of those three days I had a feeling of calmness, and everything seemed brighter, the colors seemed more vivid, and the air seemed more alive.

Yeah, I personally find it very hard to meditate, but I’m sure it works, you just need to practice.

It’s like going to the gym, it’s a habit that you quietly do every day. I remember I asked the guy who was doing the course in Rochester what was the purpose, and he said that eventually, the goal you should be aiming for is to be doing 6 hours of this every day. I was shocked, that’s a job, an unrealistic goal! [laughs]. But it helps, definitely.

What is home to you?

Home is wherever Allegra, my wife, is.

That’s very nice. And what is your happy place?

Oh, I have lots of happy places.

So, you’re a very happy person.

Not really, actually! You know, I’m an actor, and there’s a reason why the collective noun for a group of actors is a “moan” or “whinge” of actors – because we complain a lot when we get together! [laughs].

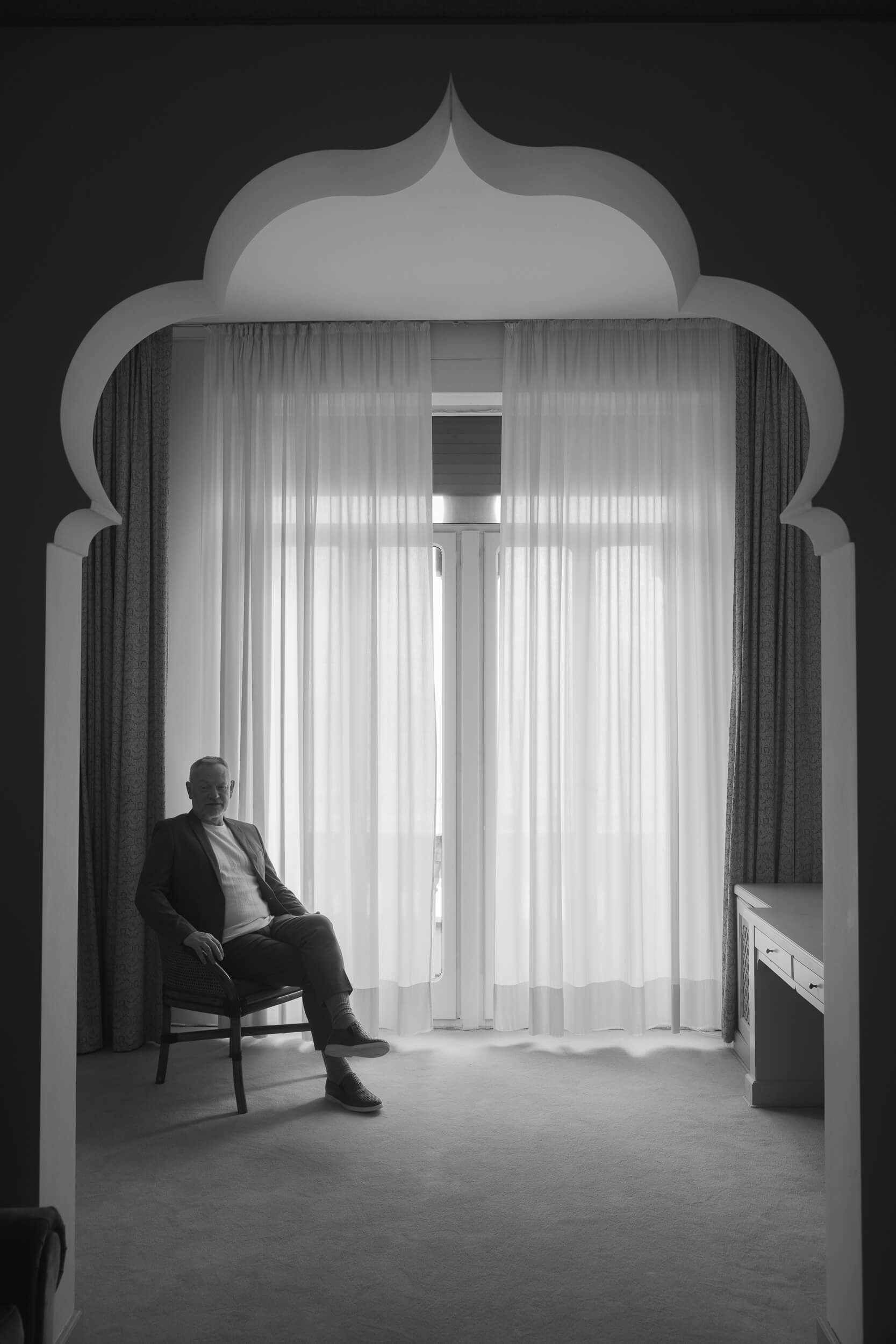

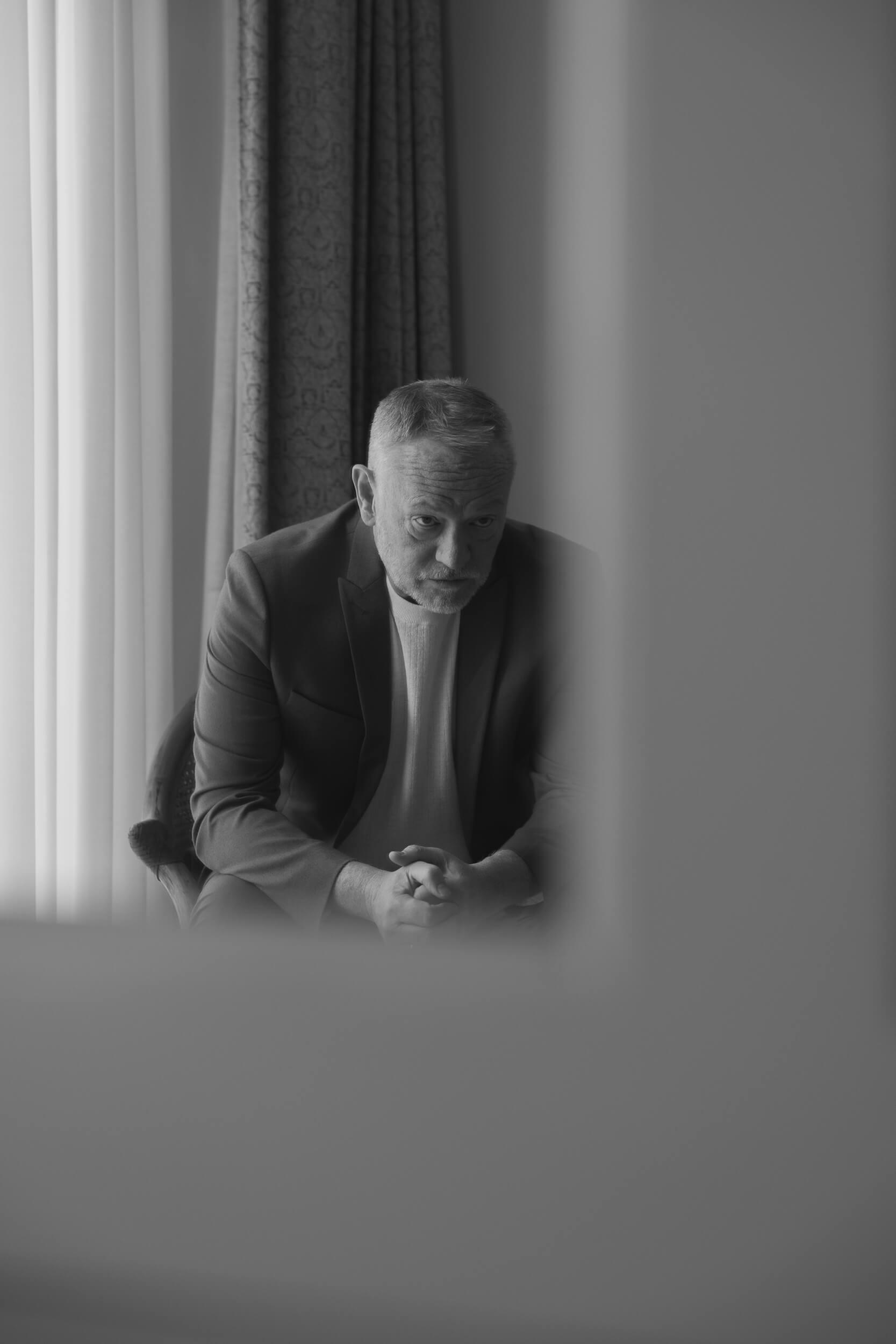

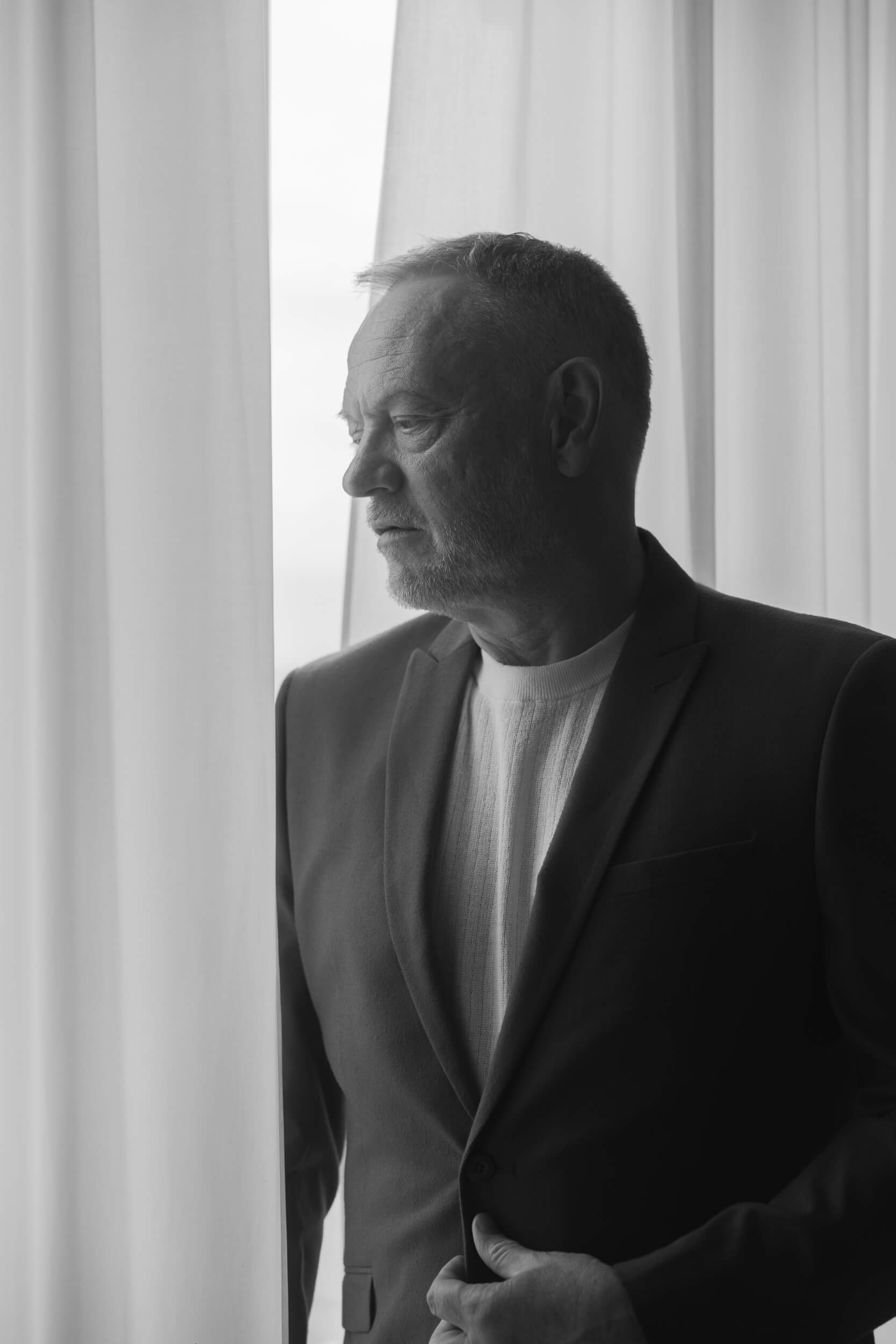

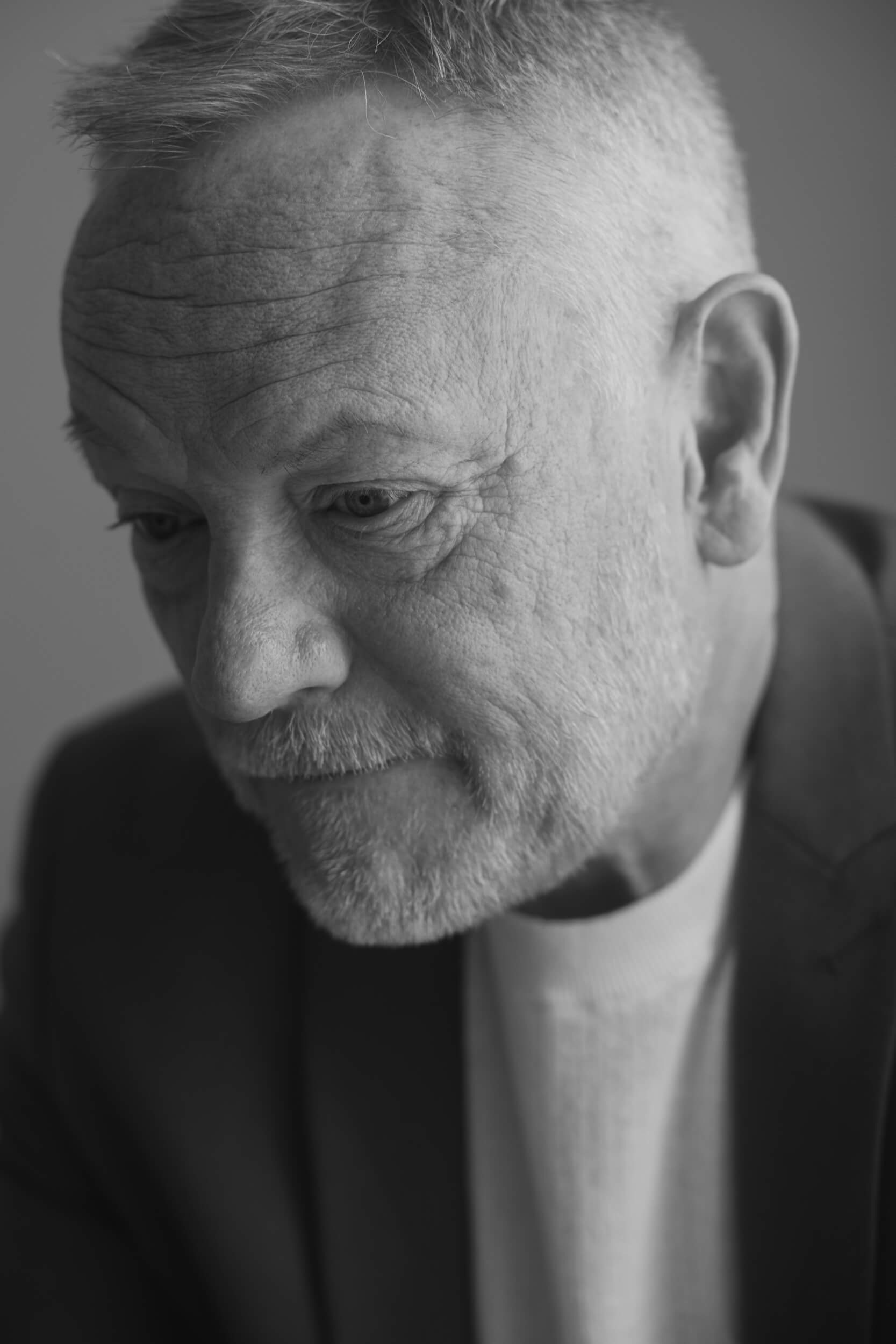

Photos by Johnny Carrano.

Location: Hotel Excelsior.