Venice, at the end of August, is a whole different story.

Venice, with the Film Festival, is truly something out of the ordinary.

By hosting a temporary microcosm – one that nonetheless leaves its mark in the months to come, until it repeats itself again, cyclical, always the same yet always somehow different – Venice becomes a land brimming with opportunities within everyone’s reach. Because the Film Festival brings the unimaginable right before our eyes: the surreal universes of the greatest films, those untouchable figures you’d never expect to encounter.

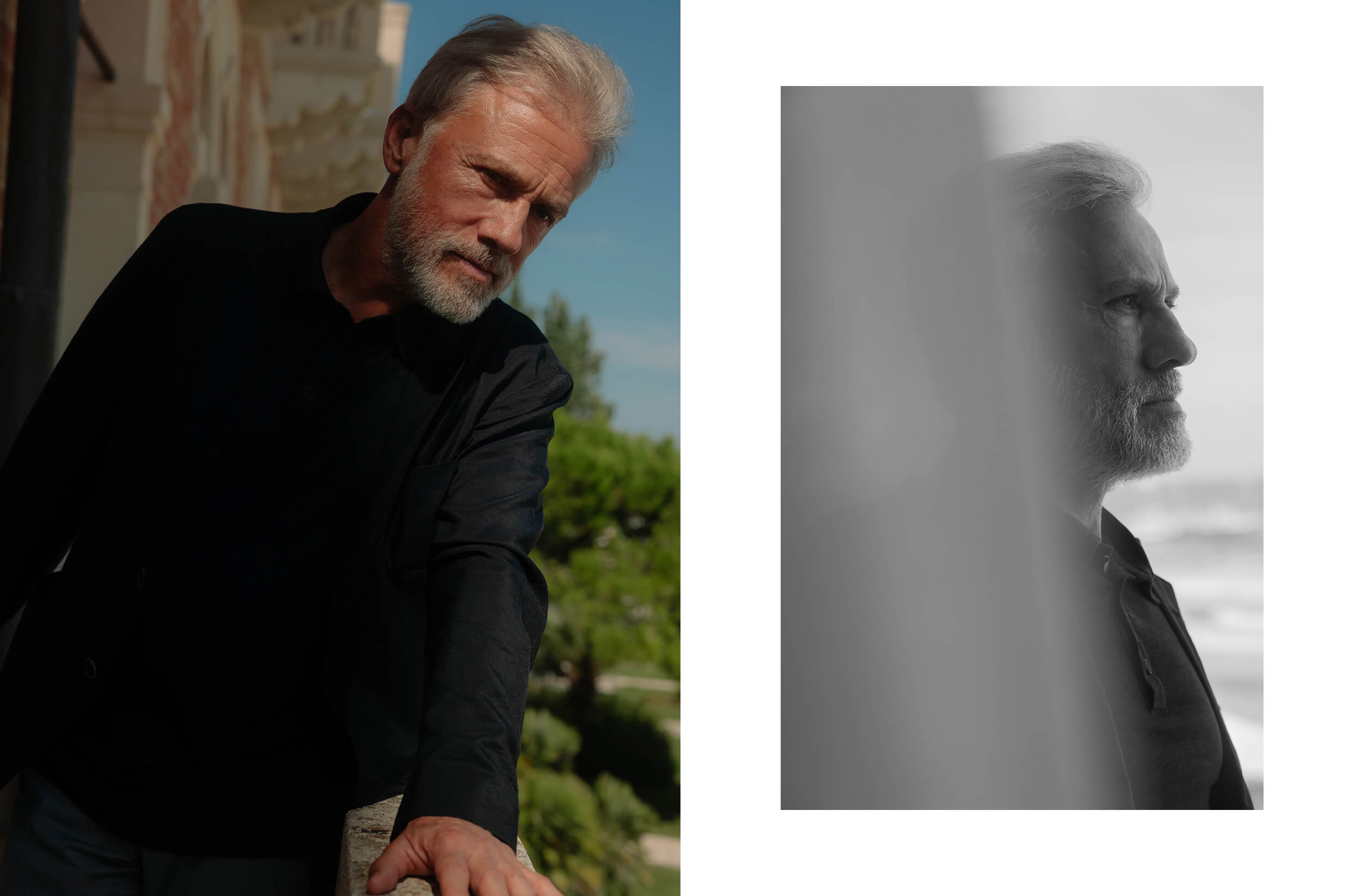

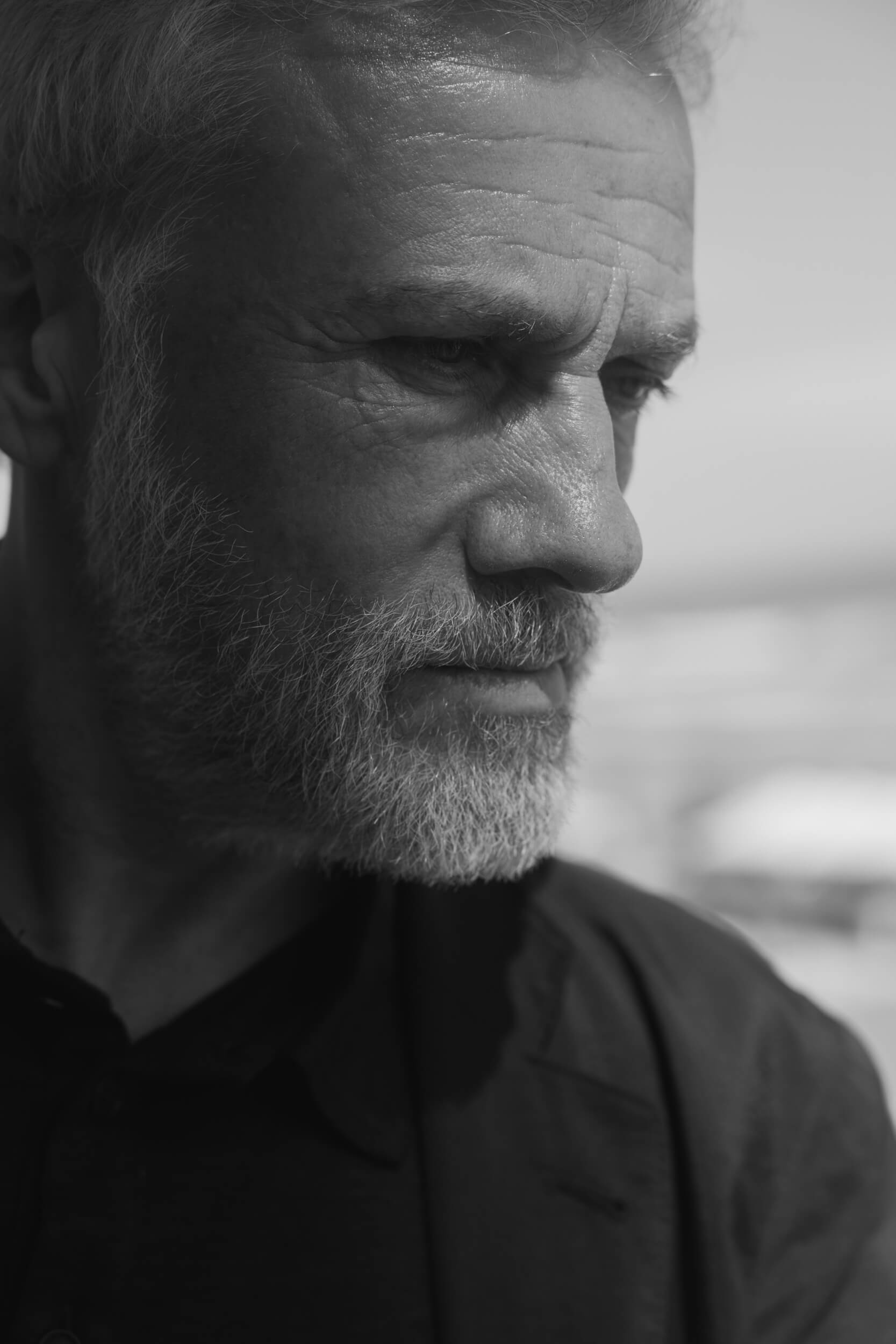

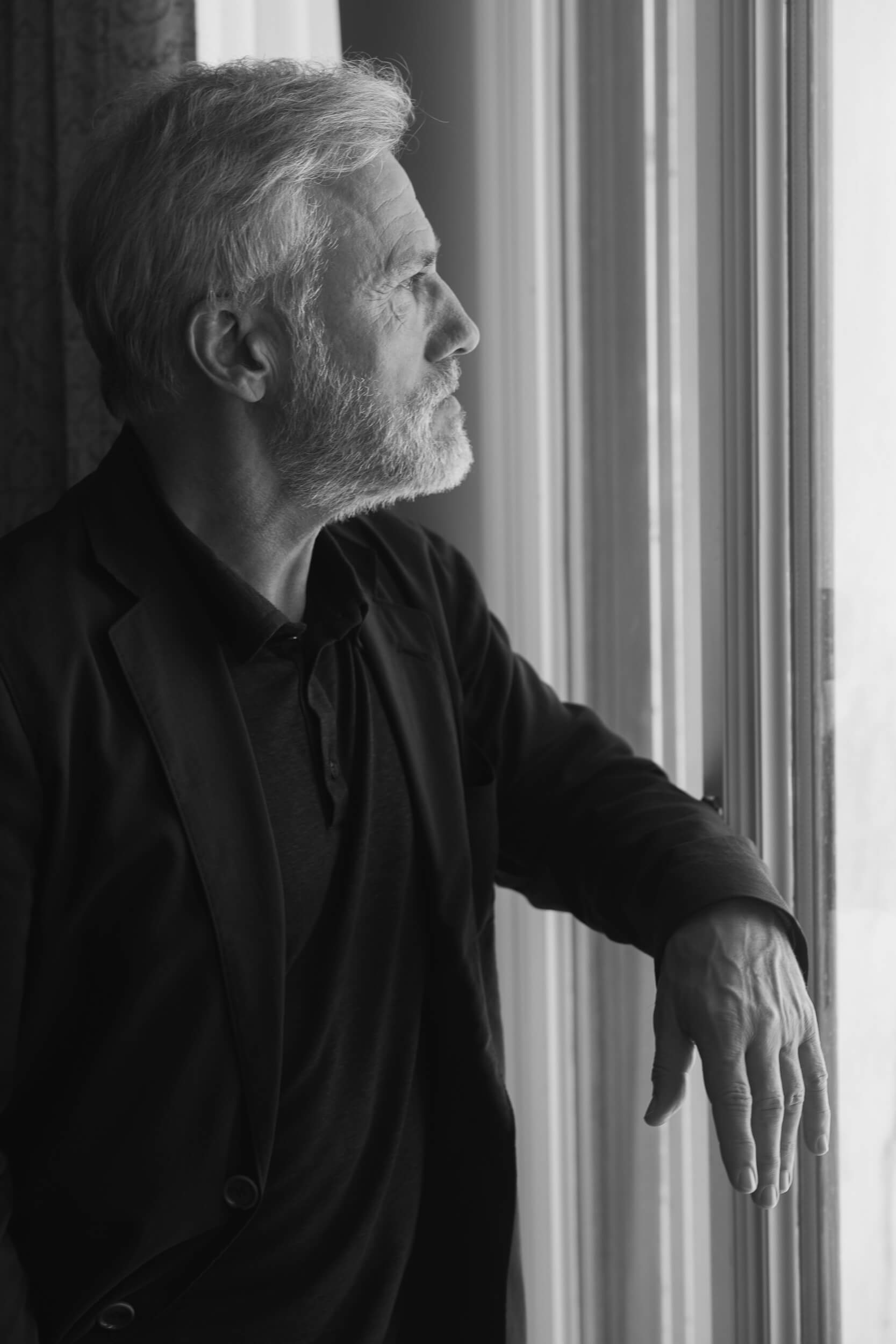

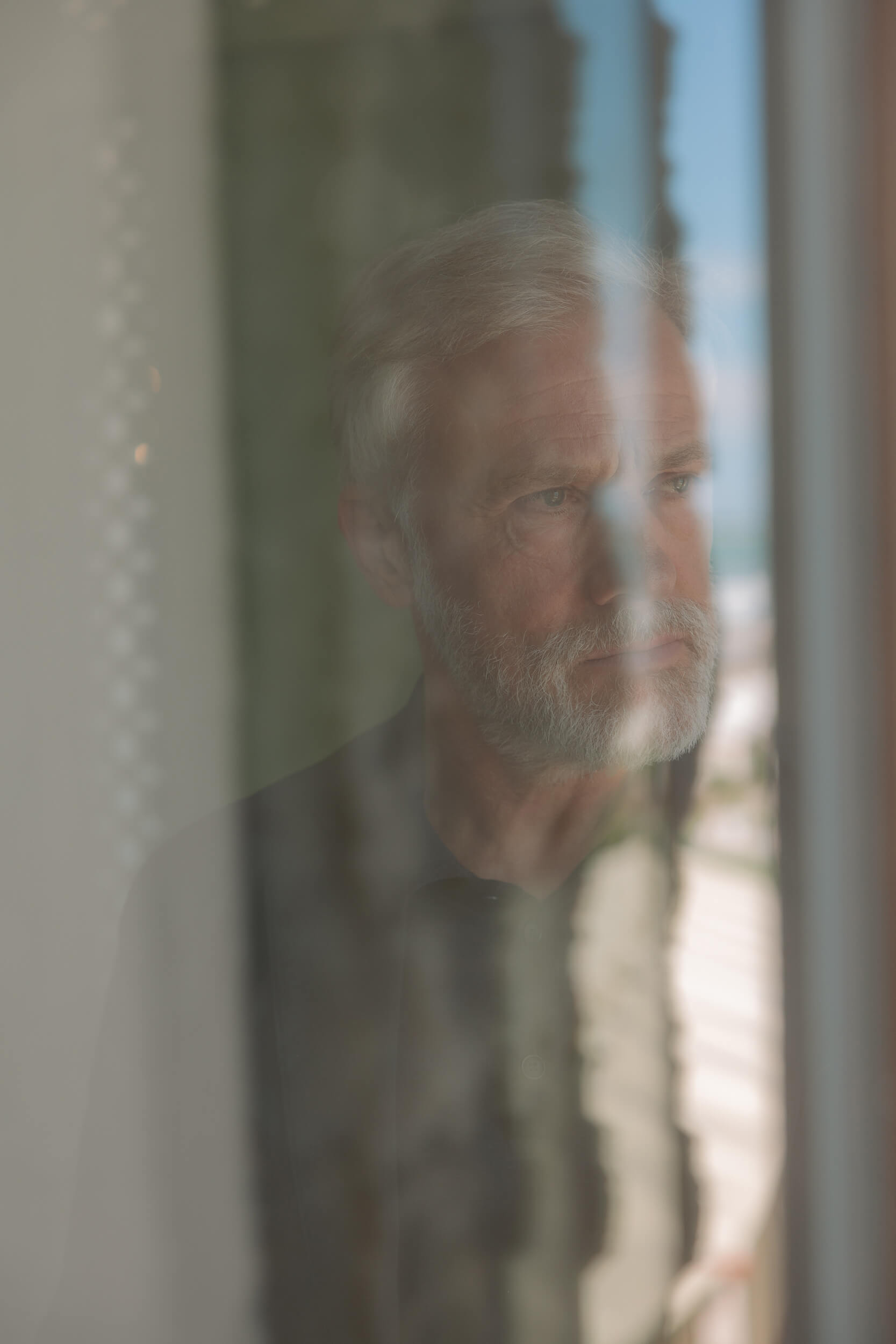

Our September Cover Story is a tangible example of what happens in Venice during the Festival: Christoph Waltz, seated at a sea-view café table across from me, told me about his Venice and his Herr Harlander. In Guillermo Del Toro’s “Frankenstein”, Christoph plays a film-only character: an arms dealer who made his fortune trading with warring armies, fascinated by Victor Frankenstein’s [Oscar Isaac] scientific experiments in battling Death in its permanent state.

My conversation with Christoph was revitalizing: we spoke not only about “Frankenstein”, but also about stories, methods, talent, feelings, religion, and humanity. A dialogue in crescendo that only Venice – and only an icon – can truly deliver.

How are you doing, Mr. Waltz? Having a good time in Venice?

I’m good! Venezia is not of this world. It is somewhere in the upper, higher spheres. I think I was about 10 or 12 when I first came to Venice with my family, and I’ve been here not every year, but almost. On the day before yesterday, we came from Milan, and when we got to Mestre, my heart started beating so fast, I started to feel that I was getting excited. You know, the train goes very slowly, and when we were heading out of Mestre, across the bridge, I started to whisper to myself, “We’re going to Venice, we’re going to Venice”. Every time I see Venice, and it makes no difference what the weather is – sometimes it’s even more beautiful when it’s grey and rainy – I think that it can’t be possible that humans at one time in history had sensed how to build a community and a life and an environment that is extraordinary.

Literally out-of-the-ordinary, yes, I agree. This place is special and let’s hope it survives against climate change, for instance.

Yeah, and tourism, which is insane and destructive. Others want to see Venice too.

Speaking of “Frankenstein”, now, I watched it a couple of days ago and loved it, from the visuals to the performances, to the characters’ narrative arcs. You know, Guillermo Del Toro very often blends beauty and horror, tenderness and violence in his movies. How did he guide you in shaping Harlander so that he would not be just a simple villain, but a man whose choices reveal the tragedy of his time?

Guillermo wrote a pretty good script, that’s what he did, and that’s really what a script should do – it should give you the scope of it. Dialogues are “just” words, you know. Do they mean something? Most definitely, but it’s the overall, the awkward, hybrid situations of a film script that really matter. It’s not literature, but it’s not an instruction manual either. When they say, “Oh, just be yourself, you can do anything!” I say, “No, no, no, it’s not that easy”.

It’s not even that easy to be yourself.

Well, apart from that, exactly! You know, a great scriptwriter suggests all that he or she wants to feel and experience when they see what’s on the screen, and it’s difficult to do. And that’s how Guillermo communicates in stories, in images, and we talked a lot – he’s not a very shy person, he tells you what he thinks, what his ideas are.

“…it’s the overall, the awkward, hybrid situations of a film script that really matter.”

The film explores themes of abandonment, responsibility, and the thirst for recognition. How does Harlander fit in this? Do you think he, in his own way, also longs for power or recognition as a substitute for love?

Yes, I agree with your beautiful interpretation. Your projection is what this is all about, and I’m glad you’re saying that, but you know what I think? My interpretation doesn’t count because I’m the one who plays that.

Fair enough!

At some point in the film, the Creature says that “violence is inevitable, and you get killed only for who you are”. Do you see his story as a metaphor for our contemporary fears and prejudices against what we perceive as “different”?

Yes, definitely, but it does not differentiate this story from any other story that is based on real human consideration. All great stories reach into our culture, subconscious, past, fears, hopes, anxieties about the future. That’s what they’re for, that’s why they were invented many thousands of years ago – to give us an opportunity to project and occupy ourselves with our existence. Otherwise, we could very well be replaced by AI because, evolutionarily, we wouldn’t make any difference.

Another haunting question of the story is: “Where does the soul lay in a body, what is it that animates the limbs?”. I thought about this a lot after watching the film, and wondered: if the soul can be hidden in something that appears monstrous, what does this say about how we judge others in life?

Are you religious?

Not really.

But you grew up catholic.

Yes, I did.

You know, when you talk about the soul that animates the limbs, it’s a beautiful thought, and maybe ultimately it does, but I think it’s the soul that gives us a direction, it’s the soul that qualifies the energy that comes from the brain and from the physiological cycles that animate the limbs. So, I kind of shy away a little bit from speculating about what the soul can do and what it can’t do. I understand that religion doesn’t, and for good reasons, but I’m personally more careful.

“I think it’s the soul that gives us a direction, it’s the soul that qualifies the energy that comes from the brain and from the physiological cycles that animate the limbs.”

Also, there’s a line in the film: “Pain is evidence of intelligence.” How does this idea resonate with you, both in the film and in your own reflection on human experience?

It doesn’t, I think it’s romantic bogus [laughs]. It’s a 19th century concept of the artist that only pain can produce art or, in this case, intelligence. If pain is evidence of intelligence, then the Dalai Lama is stupid? No, I think he’s not.

Perhaps, this, again, is a concept rooted in religion, tied to the notion of sacrifice and to the value Catholicism places on it.

Yeah, the Church operates with pain because it gives them power – they can relieve you of the pain and only they can do it, and if you let them, they are willing to consider you intelligent. But even with the Church, I think it’s infinitely more complex than that, that’s the layperson’s prejudice about the Church, in a way.

Anyhow, I disagree that pain and intelligence are related. Pain and experience are, and how you process an experience has something to do with your intelligence.

Interesting, I agree.

You’ve played many complex characters torn between morality and pragmatism. What was uniquely challenging about embodying Harlander compared to your previous roles?

I’m going to say the script, again. I don’t make decisions, and I don’t make judgments either because it doesn’t help me. My opinion is irrelevant to you, that’s why I was happy about your interpretation of the story, because that’s what is relevant. So, I completely disregard especially moral judgements about the characters that I play. What does the script require? What is it that I need to do? What’s the story?

I believe in the question “What is it?”.

So, you tend to be very rational when working on a character.

Well, I don’t pretend that only pain can induce art. There are requirements because the story exists, I’m not making it up, I don’t infuse the story with my feelings. Also, we live in a time where personal feelings become the measure of all things – I vehemently disagree. To a much lesser degree, it is what I try to do when I get a script. Sometimes a first impression and my feelings are an instinctual guidance, yes, but not necessarily so.

I find how I feel about something not terribly interesting – I’m a Libra, my feelings change a minute from now. I need some tangible guideline, and that’s not necessarily in the feeling.

This explains a lot about your way of working and where your skills come from.

You know, I’m very grateful to have those, but it puts a certain responsibility on me, I understand, and other than that, thank you very much, and now what? Does this give me credit forever? No. Talent is like a plant – if you don’t nurture it properly, if you put it in the wrong spot in your apartment and it doesn’t get any light, if you forget to water it, puff – there goes your talent.

And what do you hope audiences will take away from this new version of “Frankenstein” — especially in a world where ambition, war, and the search for belonging are still so deeply intertwined?

First of all, I hope that everyone starts to think or shift their thinking a little bit. Where to, I don’t think the movie should tell you because I really believe it’s about you. But it gives you a lot of opportunities. If you just watch it for the spectacle, it’s worth your money, you get everything and more, wouldn’t you agree?

Yeah, I told people, “Go watch it at the cinema”.

Yeah, absolutely, but not only for its visual opulence. Watch it at the cinema for exactly what you asked me, because it will give you a lot. And if you consider that it’s about you, you get a lot, I think.

“Talent is like a plant – if you don’t nurture it properly, if you put it in the wrong spot in your apartment and it doesn’t get any light, if you forget to water it, puff – there goes your talent.”

I appreciated the emotional depth of this story. “Frankenstein” is all about feeling out of place or rather homeless, loveless, uncomfortable in the pieces of the body that’s been given to you without you having the possibility to ask for it or choose it…

You’re talking about agency, being able to change something through your action.

The lack of agency isolates people; it’s a social question. If I’d be a true Marxist, I could now go into a long thing about the alienation of the masses, and the instrumentalization of human labour and human spirit in the service of capital. I won’t. But, you know, recognition is how little children survive – a baby cries, the mother hears it, and this is what makes the baby survive, it’s not the milk, it’s the recognition by the mother. It has been observed, not only amongst the animals, that if a creature, be it animal or human, is neglected, it will wither and die, just like the plant and the talent we were talking about a while ago. So, yes, there is an immense depth to this story.

Photos by Johnny Carrano.