There comes a moment in a writer’s life when words are no longer enough to tell just one world. New paths begin to open, distant borders are crossed, and one discovers that true wonder is born precisely when we find the courage to move beyond them. Licia Troisi — astrophysicist, author, and undisputed queen of Italian fantasy — has done exactly that: she has left behind, or rather, walked alongside dragons, magic, and imaginary worlds to dive into the rational, yet no less captivating, universe of mystery and crime fiction.

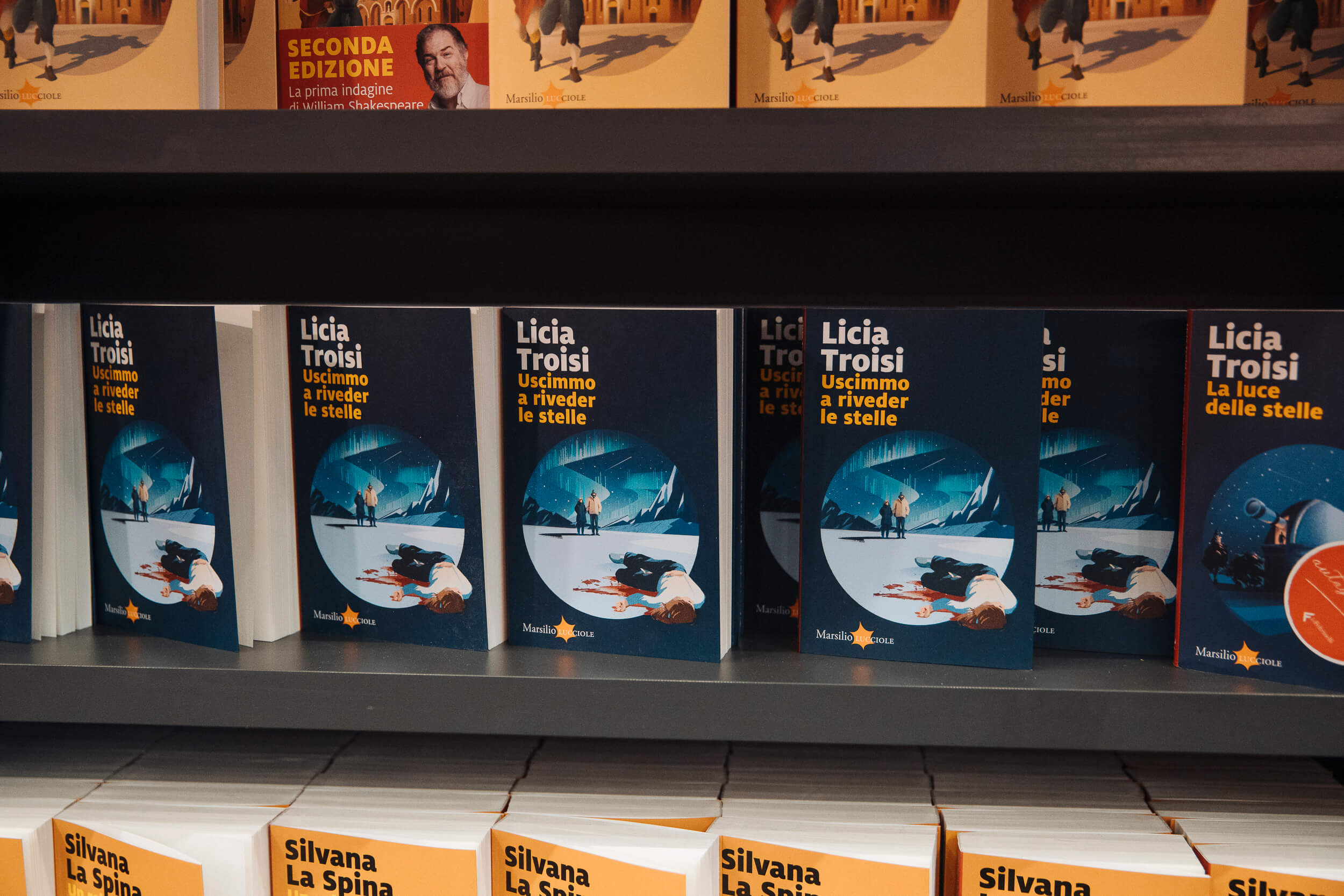

With “Uscimmo a riveder le stelle”, the second chapter in a new series, Licia takes us into a world where science meets noir, irony blends with tension, and the voice of reason coexists with that quieter, more insidious one: anxiety. In our conversation, Licia guided us through her narrative universe, revealing how a story is born when science becomes the foundation for building fictional worlds. She spoke of her methodical approach, but also of the emotions that course through it — of the inner voice that sometimes stings, and the long journey toward recognizing a personal strength she had not always seen in herself.

A dialogue that goes far beyond literature, touching on what may be the most profound aspect of human experience: the search — in all its forms — for truth, for beauty, and for the self.

It’s a great honor to have a chat with the queen of Italian fantasy, even though you’re here to present a title from a different genre, “Uscimmo a riveder le stelle” (“We Came Forth to See the Stars Again”): how is this new journey into the world of mystery novels going?

Very well, I must say. Last year, when the first book came out, I was quite worried because it felt like a leap into the unknown, even though I had already included some mystery elements in my previous books. But switching genres entirely, after 20 years of a career mainly in fantasy, was a bit strange. And yet, I must say that the reception was very, very good; so I’m really happy I challenged myself with this new experience.

It’s a story that mixes science, mystery, humor, and tension: how did you develop the writing process of this novel and the previous one? What’s your creative process like, from gathering ideas to inspiration, drafting, and post-production?

To be honest, it wasn’t radically different from what I do for fantasy. In my view, genre literature shares some core elements—mainly the importance of plot and characters. So the plot still has to be structured a certain way, maintain a good pace, mislead the reader… In this sense, the methods are similar. I always start from an idea (in this case, the astronomer detective) and, for the second book, the idea of setting the story in a scientific conference. From there, I gradually develop the characters and the plot. Before I start writing, I actually outline the story chapter by chapter. I’m a very systematic writer, so I need a lot of planning and a clear structure beforehand, which allows me to fully surrender to the narrative flow later on—that’s the part I enjoy most.

Gabriele Stelle is an astrophysicist, like you: did this character surprise you during the writing process, or had you envisioned him quite clearly from the start?

I had a pretty clear idea of Gabriele from the previous book. Some aspects of characters can become more focused as I write—that’s happened before—but it didn’t happen with this book. I had most of it figured out from the beginning, character-wise.

Gabriele hears a little voice whispering things to him, sometimes challenging or confusing him. Is that voice real for you, too? And how do you keep it in check, if so?

It’s kind of a manifestation of my anxiety. I suffer from anxiety, so those are essentially my intrusive thoughts. In reality, in my work life, they’ve become part of my process—they help me stay focused and keep moving forward, pushing myself to do my best. I think I’ve managed to keep them in check through my passion for writing. I’ve found a place for them within my creative process, so I’m no longer paralyzed by them.

The title references a quote from Dante, who managed to capture the complexity of the human experience through science, religion, history, and culture—perhaps making him immortal and universal. How do the paths to knowledge and to hell intersect?

There’s probably a parallel with what happens to Gabriele in the book, because whenever he looks at the sky, it’s a moment of self-realization and also relevant to the case he’s solving. Given the themes I explore in these books, I’d say that hell is how we conduct research—some aspects of our version of the scientific method are overly performance-driven, and I don’t think they’re healthy for research. Since publishing this book, I’ve often met people at events who tell me how much they related to the academic experiences depicted in the story. Some even told me they left academia because they couldn’t tolerate the environment—too competitive, toxic relationships with supervisors… So maybe that’s hell.

Is there also a paradise?

For me, paradise is everything related to trying to understand the universe. That’s something truly beautiful, born from human curiosity—the desire to comprehend the world around us. That’s what we should try to preserve: the yearning for knowledge and the ability to grasp the laws of the cosmos. As for how we go about it—well, that’s something we can work on.

Can we say, then, that creating worlds, characters, and stories is a kind of science?

I don’t know if it is in general, but for me, yes. I was talking about this the other day with someone who came to one of my presentations. They said, “When you talked about your writing method, it immediately sounded like it came from science,” and that’s true. I make outlines, I’m very systematic—those are traits that come from my scientific background. But it’s not universally true; some writers take a completely different path, letting themselves be entirely carried by the narrative flow… It’s not true for everyone, but it is for me.

Science and fantasy can seem (mistakenly, in my view) like opposites, due to the contrast between the imaginary and the real. How do you view this relationship, and what does it mean to you?

For me, science has often been a source of inspiration for my stories. So I don’t see them as opposing forces—on the contrary, world-building, for me, is very much tied to science. We need to create coherent worlds, just as the universe is coherent. Our brains will believe in invented and absurd worlds as long as they are internally consistent, because we deal with an internally consistent universe. So there can definitely be a connection—it’s not always necessary, but in my opinion, anyone creating worlds is doing a bit of science.

“That’s what we should try to preserve: the yearning for knowledge and the ability to grasp the laws of the cosmos.”

What’s the scientific fact about the universe that fascinates and excites you the most?

Definitely the first detection of gravitational waves. I had even taken a course on them during my PhD, but they hadn’t been observed yet. I doubted they ever would be, even though the theory behind them—general relativity—is incredibly solid. But since they produce such a tiny effect, I didn’t think the technology would ever catch up. I actually got the news in advance because my husband was working with the team searching for the so-called counterparts to gravitational waves—when one is detected, they look to see if something also happened in the sky, in visible light, X-rays, etc. He was part of the team searching for optical counterparts, so we got the news early. It took six months from discovery to announcement while they confirmed the result, and it was solid. Now it’s routine to detect gravitational waves every day.

What book or books are on your nightstand right now?

I’m reading a science fiction book, “Big Time” by Jordan Prosser. It’s a fictional story told by a journalist who travels with a band, but there’s a sci-fi element—it’s set in the near future, 2040, and in this future, there’s a drug that lets you see the future. I’m still at the beginning, but I’m really getting into it.

What does it mean for you to feel comfortable in your own skin?

It’s a long process, one I’m still working on. I’ve struggled all my life with body image. For a long time, I didn’t like myself, and even now I struggle to separate how I see myself from the number on the scale. But I must say that lately, I feel more aligned between my physical self and my inner image of myself—so clearly, I’m making progress in that regard.

What’s the last thing you discovered about yourself, thanks in part to your work?

I’m going through a period of discovering a lot about myself. I’m learning to accept that I’m good at something. That was really hard for me—to say to myself, “Yes, you did this well,” without feeling arrogant or overconfident. I’m learning that. I’m also discovering a lot of strength. I always saw myself as a very fragile person—but I’m not. And that’s a beautiful realization.

Your happy place?

The forest. I live fairly close to the woods, and I love going for walks there. Right now, I can’t go very often because I fractured my ankle and need to be careful. But when I’m surrounded by nature, I feel everything come back into balance.

Have you already reread “The Name of the Rose” this year?

Yes, yes—I don’t remember if it was December or January, but I’ve already reread it.

Photos by Luca Ortolani

Thanks to Marsilio Editori